Machine learning predicts subtypes of Parkinson’s disease

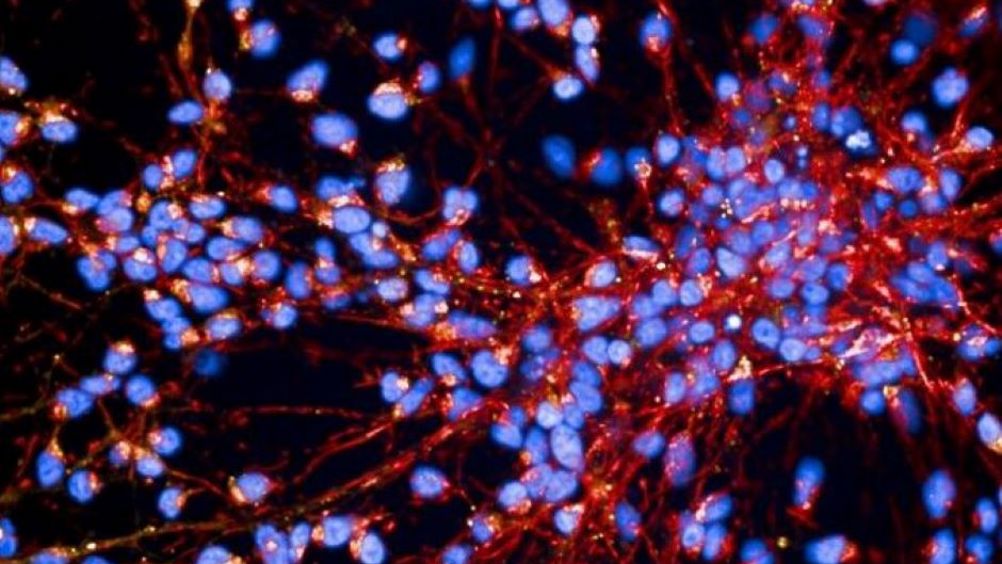

Machine learning can predict subtypes of Parkinson’s disease using images of patient-derived stem cells, an advance that could lead to personalised medicine and targeted drug discovery.

Carried out in collaboration between the Francis Crick Institute, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology and Faculty AI, the team’s research has shown that computer models can classify four subtypes of Parkinson’s disease, with one reaching an accuracy of 95 per cent and showing potential for personalised therapy. Their work is detailed in Nature Machine Intelligence.

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative condition impacting movement and cognition. Symptoms and disease progression vary from person to person due to differences in the underlying mechanisms causing the disease.

Until now there hasn’t been a way to accurately differentiate subtypes, which means people are given nonspecific diagnoses and do not always have access to targeted treatments, support or care.

Parkinson’s disease involves misfolding of key proteins and dysfunction in the clearance of faulty mitochondria, the source of energy production in the cell. Most cases of Parkinson’s disease start sporadically, but some can be linked to genetic mutations.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

UK Enters ‘Golden Age of Nuclear’

Anybody know why it takes from 2025 to mid 2030's to build a factory-made SMR, by RR? Ten years... has there been no demonstrator either? Do RR...