Vital-signs monitor could be produced for lower costs

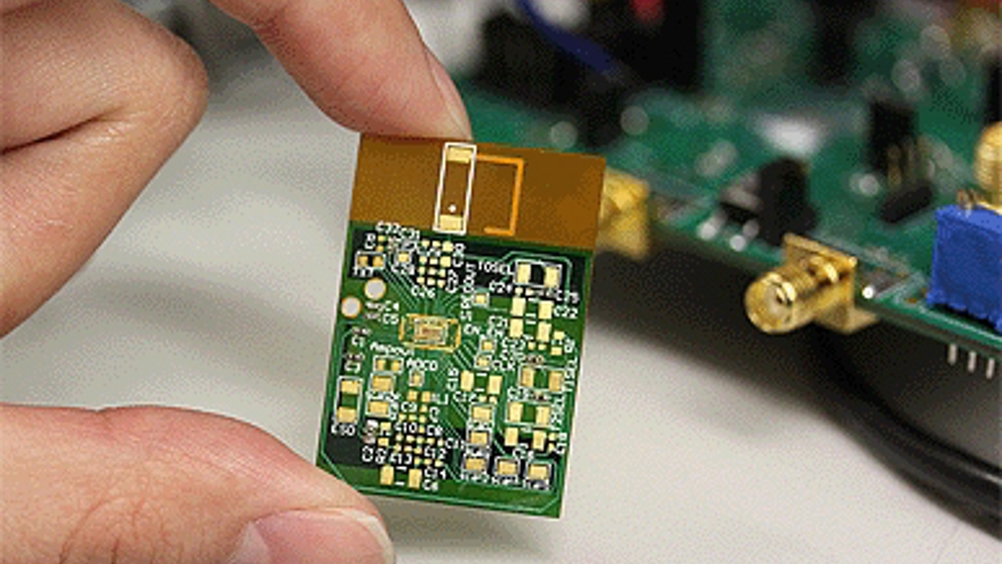

A new vital-signs monitor developed by engineers at Oregon State University is claimed to overcome the limitations of current devices as it is small, powerful and can be manufactured in high volumes at low cost.

A patent is being processed for the monitoring system and it’s now ready for clinical trials, the researchers said in a statement. When commercialised, it could be used as a disposable electronic sensor, with many potential applications due to its performance, small size and low cost.

Heart monitoring is said to be one obvious candidate, since the system could gather data on some components of an EKG, such as pulse rate and atrial fibrillation.

Its ability to measure EEG brain signals could find use in nursing care for patients with dementia and recordings of physical activity could improve weight-loss programmes. Similarly, measurements of perspiration and temperature could provide data on infection or disease onset.

‘Current technology allows you to measure these body signals using bulky, power-consuming, costly instruments,’ said Patrick Chiang, an associate professor in the OSU School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. ‘What we’ve enabled is the integration of these large components onto a single microchip, achieving significant improvements in power consumption. We can now make important biomedical measurements more portable, routine, convenient and affordable than ever before.’

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Pipebots Transforming Water Pipe Leak Detection and Repair

Fantastic application.