There were some slivers of good news in the latest annual state-of-the-nation EngineeringUK report released this week.

The country’s engineering turnover is up, more young people see an engineering career as desirable, and almost as many girls as boys now gain a GCSE pass grade in physics.

Unfortunately, there were also plenty of depressingly familiar statistics about the need for more engineers, the lack of understanding and approval of engineering careers by parents and teachers, and the number of young people choosing not to enter the profession.

One of the typically trumpeted statistics was the salary premium that engineering graduates enjoy: their average starting salary was £26,500, 20 per cent higher than the average for all graduates.

The problem is that this statistic, like most used to illustrate the industry’s skills issues, doesn’t tell the full story. There is no single problem called “the engineering skills shortage”. There are a series of different challenges facing different companies in different sectors.

Salaries are often highlighted as a possible reason why more people don’t enter the profession, and industry bosses like to point to the premium figure featured in the EngineeringUK report as an argument against this. And, despite many opinions to the contrary, the median salary for an engineer is actually greater than that for a solicitor, chartered accountant or architect.

But median salary isn’t everything. The brightest, most ambitious young people – the ones the top engineering companies are really after – know they can earn top salaries, not just average ones.

So another report that came out this week – the High Fliers survey of the 100 most popular graduate employers – may well be more useful to top engineering firms if they start to see a gap in their own recruitment campaigns.

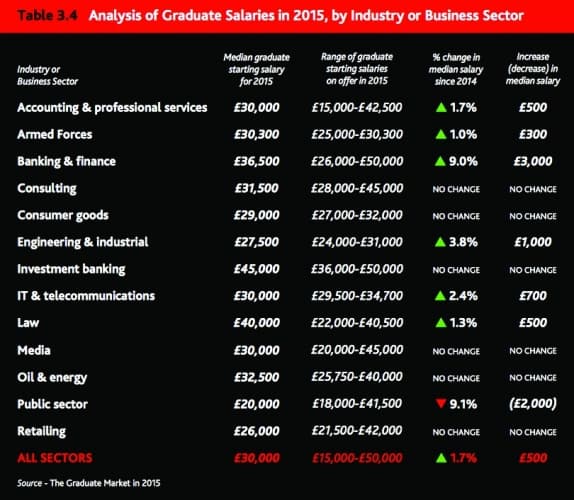

The average starting salary at these most sought-after firms was a record £30,000. For those which fell into the engineering and industrial category (the likes of BAE Systems, Jaguar Land Rover and Siemens), the figure was just £27,500, less than in every other sector except retail and the public sector.

And the divergence of top salaries was even greater. The most you can earn as a graduate at a top engineering firm is £31,000. In accounting, finance, law, media, retail and the public sector, the best candidates will land over £40,000.

Given their popularity, it’s likely the engineering firms in this survey have likely filled their graduate schemes without difficulty and haven’t felt the need to offer higher salaries over the last few years.

But as the economy continues to recover with the service sector steaming ahead of engineering and manufacturing, there’s a real danger the big firms will face their own skills shortage if they can’t keep up with the appeal of other top employers.

Of course, most young people will never start their careers on such high salaries. And money isn’t everything, especially to the kind of young people likely to be inspired by the intellectual challenge of engineering.

Yet the wider image of engineering as a leading profession to which all young people should aspire is damaged by statistics like these. Because career decisions take place so early, engineering must present itself as an industry that offers as many opportunities for success – including monetary success – as its rival professions.

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Well let´s do a little experiment. My last (10.4.25) half-yearly water/waste water bill from Severn Trent was £98.29. How much does not-for-profit Dŵr...