I admit it - I’ve secretly been overjoyed by the number of articles I’ve seen recently calling out the shocking lack of diversity in our boardrooms. As both a proud mother of three teenage daughters and an executive at a global energy company, I believe gender equality in our boardrooms will only come through social equality. And that starts with us removing gender stereotypes in our homes and classrooms.

We know that bridging the gender pay gap could increase the UK’s GDP by billions of pounds in the next 10 years, adding nearly one million females to the workforce. Yet women continue to be least represented in higher-paying sectors, including science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM). In fact, the UK still has the lowest percentage of female engineers in Europe, with less than one in 10 engineers being female.

Interestingly, research shows that the more gender equality a country has, the less likely it is to have women in STEM occupations. The fact that there are many countries – especially in the Middle East and Asia, for example – with high female representation in STEM, completely debunks any sort of claim that girls have “less aptitude” for STEM professions. This is simply not true.

In many countries with rapidly changing economies, women are taking on careers in STEM subjects to advance more quickly and maximise their earning potential. In our recent graduate hiring campaigns at BP, the highest representations of female engineers were in Azerbaijan, Egypt, Indonesia and Oman.

So, what can we learn from other countries to change how young girls and women view STEM subjects and careers in the UK?

Stop gender stereotyping

In many cases, according to Saadia Zahidi, author of Fifty Million Rising, Muslim women are pioneering their role in the workforce, so they don’t have preconceived stereotypes about whether tech jobs, for example, constitute 'feminine' career goals. Recently, the OECD used the Programme for International Student Assessment to understand students’ own proclivities around maths and science. The studies showed overwhelmingly that girls felt “helpless when performing maths problems”, yet they scored only about two points on average lower than boys. So, it’s clear that girls are much better at maths than they think they are!

What’s needed is a culture change to reverse our deeply-rooted stereotypes. Campaigns like “Inspire the Future” have highlighted this challenge. This is slowly happening, but of course is easier said than done. Parents and teachers of girls need to be especially conscious of the impact they have on their perceived abilities. Confidence in STEM subjects takes root in our homes and classrooms – it means providing affirmation and reinforcement and not allowing others to define what we are and are not ‘good at’.

https://www.theengineer.co.uk/eastern-promise-gender-lessons-from-the-islamic-world/

It’s never too early for STEM engagement

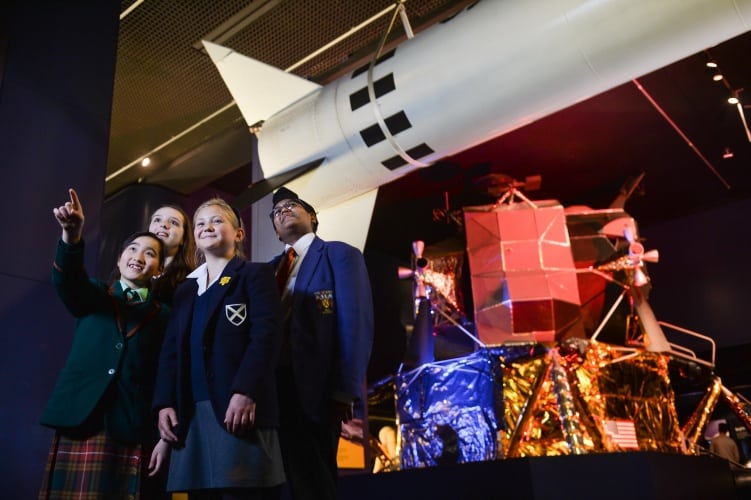

Given that perceptions of STEM subjects are shaped so early on, many initiatives aimed at getting women into STEM subjects at age 16-18 are coming too late for some. Gender stereotypes are defined between five and seven years of age, so it’s especially important that we have STEM initiatives geared towards primary school children. We also want to engage children through hands-on activity, to really open their eyes to the possibility of a STEM career. An example of this is the BP Ultimate STEM Challenge, a nationwide competition for 11 to 14-year-olds, run in association with the Science Museum Group and STEM learning. Now in its fourth year, the competition is designed to help young people develop their creativity, problem-solving skills and employability, by addressing a real-world STEM challenge.

Representation and role models

Finally, if we are going to get over the gender stereotypes about tech and engineering jobs, we must have strong female role models for young girls. In support of the International Women’s Day 2018 #PressforProgress campaign, we highlighted some of the inspirational female leaders that work within our company and what progress means to them. We need to ensure we create a work environment in which women at all levels can thrive, and ensure we are giving these women platforms to be visible.

Alongside Microsoft, we have developed the Modern Muse programme, an online platform that will empower girls everywhere to make more informed career decisions. Girls, aged eight and over, can learn about the career paths and education of profiled ‘modern muses’. They can choose to follow any number of registered muses and can create networks and identify future opportunities. By connecting with successful women - at a young age - it is hoped that this will inspire and help them make informed decisions about their future career choices, long before they make decisions around GCSE or A-level subjects.

What’s becoming apparent is that some of our Western gender stereotypes in the classroom, at home and in the workplace, don’t necessarily apply to other countries. Several Muslim countries have filled more than half of their STEM jobs with female workers. To quote The Atlantic: “It’s not that gender equality discourages girls from pursuing science. It’s that it allows them not to if they’re not interested”. While this freedom of choice is not something we would ever want to curtail, overcoming gender stereotypes and bias from a young age is something that we must achieve, so that the next generation of women engineers - and society at large - can reap the benefits.

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...