Much has been made of UK engineering’s response to the pandemic, and rightly so. The way in which organisations across the spectrum have repurposed operations to produce vital medical equipment has been an inspiring reminder of the capabilities of the manufacturing base, and more generally of the importance of engineers to our society.

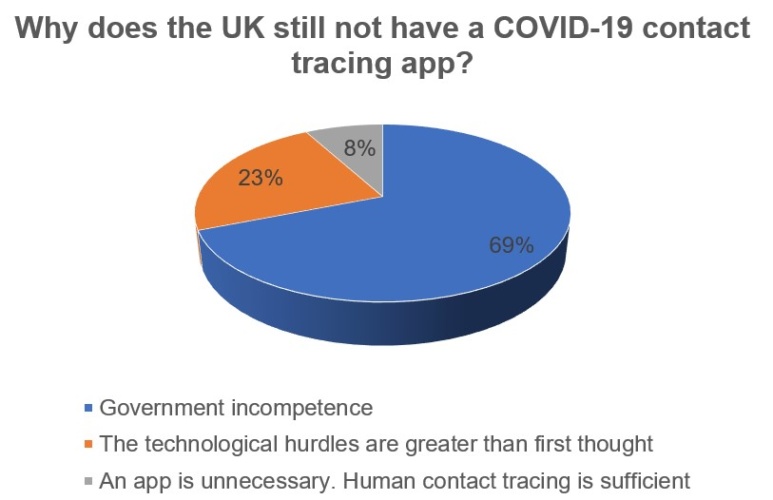

However, whilst the stories of aircraft manufacturers turning their hands to ventilator production might be a cause for celebration, the UK’s failure so far to deploy a working COVID-19 track and trace app marks a spectacular low point in our ability to apply technology to the challenges we face.

In the early months of the COVID-19 crisis health secretary Matt Hancock said a digital contact tracing app would be key to easing restrictions whilst keeping people safe and yet – almost six months on - whilst Germany, Ireland and a number of other European neighbours have already launched their own COVID-19 exposure apps – the UK is reliant on an “army” of human contact-tracers.

The government’s initial plans to develop a centralised contact-tracing app (announced on May 5th) were abandoned in mid-June owing to compatibility issues with Android and Apple devices, and it is now working with Apple and Google on an alternative design that it has warned may not be available until the winter.

In the meantime, the existing track and trace system - despite being repeatedly hailed as “world-beating” by the prime minister – is thought to be falling well short of what’s required; with health bosses in some regions warning that the system is failing to reach more than 50 per cent of contacts.

According to modelling carried out by researchers from UCL and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (reported in the Lancet) if the UK is to avoid a winter peak even worse than that seen in April, and – critically - push ahead with the September school return, both testing and contact tracing will need to be scaled up significantly.

Against this backdrop, and the pressing need for a solution, it’s hard to view our failure to roll out a system that piggybacks on the smartphones that are owned by an estimated 80 per cent of the UK population as anything other than a spectacular failure to tap into the benefits of an existing technology.

None of this is easy, and the technical challenge of developing an app that gathers enough data to be useful without invading people's privacy should not be underestimated. But neither should it be beyond the wit of a government purportedly skilled in the world of big data. As an aside, given our general willingness to surrender our privacy in return for the use of a host of free apps, it's possible that selling a contact-tracing app to the general public - widely viewed as one of the key challenges to rolling out a digital contact tracing system - might not be as difficult as some have suggested.

Perhaps this is all unfair. Perhaps a truly “world beating” UK test and trace app will emerge – later than planned, but free from the imperfections and teething problems of other systems. But with no firm commitment to a launch date that seems unlikely. And whilst the calls from experts are growing louder, the urgency that characterised the government’s early talk of an app has all but vanished.

Please do join the debate by submitting your comments below the line. Please note that all comments are moderated.

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...