It struck me that there’s a certain irony that you can’t find one of the world’s largest makers of communications satellites using satnav. Suffice to say that should you ever find yourself visiting EADS Astrium’s Portsmouth facility, don’t follow the Google Maps directions. You will end up at a motor-home dealership, where they will give you a funny look when you ask where the satellite factory is.

Once there, it was on with the flattering booties, shiny jacket and hairnet and into the humming, purposeful quietness of the clean room, to see an instrument whose twin is soon to make its trip into space aboard the METOP B satellite. This enormous chunk of hardware, operated by the pan-European organisation Eumetsat, will monitor weather conditions as it sweeps over the globe from pole to pole twice a day.

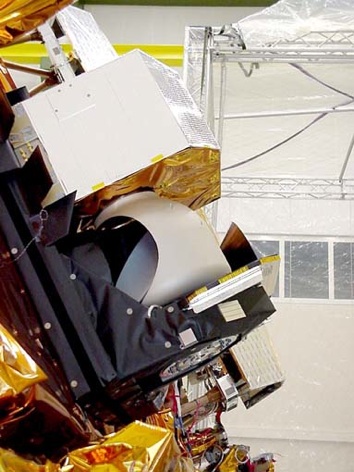

The Microwave Humidity Sounder (MHS) sits on a plinth about a metre square, which isolates it from the body of the satellite which holds it. In the clean room, the plinth is bolted onto a series of springs and dampers which hold it into the base of its storage crate; this particular instrument, although not scheduled for its own launch until 2018, has been prepared in readiness to ship out to Baikonur in case its twin, which is due for launch on 17th September, suffers any problems. ‘This could fly; it’s ready to go,’ said project manager Ian Stewart.

What seems slightly odd is that this MHS is far from new. In fact, explained Stewart, it’s 11 years old, and has been sitting in a clean room cupboard, locked into its shipping crate, since 2001, emerging once a year for testing to make sure that it still functions. Astrium built five MHS instruments, Stewart said, of which three are currently in orbit, on the American NOAA 18 and NOAA 19 satellites (launched in 2005 and 2009 respectively) and the European METOP A, launched in 2006.

‘The thing is, the instruments had to be built together, to ensure that they worked the same way,’ Stewart said. ‘We couldn’t build one now. Component tolerances have improved so much: if you’d bought a resistor, say, in 2000, it would have a resistance within a certain percentage of its rated value, but if you bought the same rating today it would be much tighter. With the cumulative effect of that from all the components, the instrument wouldn’t be measuring in anything like the same range.’

MHS measures the structure of water vapour in the atmosphere, explained Brett Candy of the Met Office, who uses METOP and NOAA satellite data in compiling weather forecasts. ‘Combined with the data from another instrument on the satellite that measures temperature, it tells us about the levels of water vapour at different altitudes,’ he said, ‘and that gives us information about where it’s likely to be foggy, for example. It’s also very good at identifying heavy rainfall, so it can be used, for example, to provide warnings as hurricanes and storm systems develop.’

The core of MHS is a rotating carbon-fibre drum, with an elliptical opening in one side. Inside this drum is an oval piece of aluminium, set at an angle so that it reflects microwave radiation reaching the instrument from directly below into a housing that contains optical detectors and electronics to analyse their readings. ‘The drum sweeps, rather than being open all the time, because that self-calibrates the instrument for temperature,’ said Stewart. ‘When the opening is pointing into the satellite, it’s looking at a magnesium alloy sheet on the mounting board, and that’s at a constant temperature. When it’s looking out at 90° to the satellite, it’s pointing into space, and that’s also at a constant temperature. That means that it can adjust to the temperature when it’s pointing at the Earth — and it makes those adjustments every time it rotates, every few seconds.’

The microwaves it is detecting are emitted from the surface of the planet (actually reflected, as they originally come from the Sun) and rise through the layers of the atmosphere. As they encounter water molecules, some of the microwaves are absorbed, causing the molecules to vibrate; the frequencies which are absorbed are characteristic to this particular vibration. MHS measures in different frequency bands to give a series of readings which, when combined with temperature data, show how much water vapour is present at various levels in the atmosphere.

Because there are currently three MHS instruments orbiting the earth along different polar trajectories, the data can show how humidity develops over time in a specific location, and hence can be used for forecasting, said Candy. The METOP-A satellite contributes 24 per cent of the data used for Day 1 NWP (numerical weather prediction) forecasting — the prediction of the weather over the next 24 hours. It’s the largest single contributor, with total contribution from space monitoring amounting to 64 per cent and direct in-situ observation from weather balloons, aircraft and surface weather stations on land and sea making up the other 36 per cent. ‘The only way to get direct, in-situ readings of humidity in the atmosphere is from sondes [monitors on balloons]’ said Candy. ‘And those are limited in number, plus they’re only launched from land.’

Work is now underway on the next generation of microwave sounders, which will incoporate their own temperature sensors and will measure across 25 frequency channels. ‘It’ll be about the same size as MHS — maybe a little larger — and will consume more energy,’ Stewart said, ‘but it’ll generate much more information.’ This, in turn, will lead to more accurate weather forecasting and more data for climate modelling, Candy added.

With one MHS currently crawling to a launchpad in Baikonur atop a Soyuz rocket and its sibling safe in its crate in Portsmouth ahead of its launch in five years time, the rest of this decade should see our knowledge of dampness in the atmosphere grow considerably. Something to think about, next time you’re stuck in the fog. As long as you’re not trying to find Astrium in Portsmouth, that is. Give the motor-home dealership my regards.

UK Enters ‘Golden Age of Nuclear’

The delay (nearly 8 years) in getting approval for the Rolls-Royce SMR is most worrying. Signifies a torpid and expensive system that is quite onerous...