It might surprise readers to know that quite a large number of science and technology journalists suffer from social anxiety. To put it in a slightly less pretentious way: we’re a pretty shy bunch. It’s not unusual, when a number of us are at an event intended more for networking than for some announcement, to find us huddled near a corner, muttering “I hate this, I hate this,” at our buffet plates, before wishing each other luck as we venture out into the crowd to try to engage some total stranger in conversation. At this point I should probably apologise to any readers who’ve met me: I wasn’t being rude, just petrified.

Anyway, last week I found myself torn between reflecting on how monstrously lucky I am to have a job where I can spend a Wednesday evening sitting on a boat watching the landmarks of Paris drift past in the golden sunlight while sipping a chilled glass of white wine, and my usual abject terror of stumbling over my words while conducting a face-to-face interview.

I found myself in Paris to cover one of my favourite events, the European Patent’s Office’s annual Inventors’ Awards (which makes my anxiety even dafter). It’s the Awards’ tenth anniversary this year, which was probably why the EPO decided to literally push the boat out with a little extra grandeur. We could probably have done without the finger-clicking jazz singer and his doubly-inaccurate rendition of ‘An Englishman In New York,’ to be honest.

I enjoy the event so much because it gives us some great examples of a few things that can be a bit elusive: how technology can directly change people’s lives for the better; how scientists and engineers come to be working on these ideas, which often involves leaps of logic that seem far from obvious; and how their inventions can be brought to market. This year’s nominees and winners were a mixed bunch from across fields connected with engineering and medicine.

I was lucky enough to interview a cross-section of nominees (once my nerves had calmed down sufficiently). Over the next few weeks you’ll be able to read about the invention and inventors of electrochromic glass; lab-on-a-chip technology; self-healing concrete and systems for computerised eye-tracking. There was only one UK nominee this year — Luke Alphey, who invented a way of rendering mosquitoes that carry Dengue fever sterile so they can’t breed and pass their infectivity on to a next generation — but unfortunately he got stuck on a delayed Eurostar and I couldn’t speak to him.

The awards ceremony itself, including a recital of variations on Rimsky-Korsakov’s Flight of the Bumblebee played on a carbon-fibre cello, saw the industry award given to Austrian scientist Franz Amtmann and Frenchman Philippe Maugars for the invention of near-field communication, which allows smartcards, debit cards and, to an increasing extent Smartphones, to be used for payment and travel by holding them near a reader; we’ll undoubtedly hear much more about this as the ApplePay system which allows iPhones to be used directly for contactless payment is rolled out in the UK. The SME prize was awarded to a team led by Laura van’t Veer, who developed a genetic test that can determine how likely breast cancer is to spread and recur in individual patients; which allows them to make an informed decision on whether it’s worthwhile to undergo gruelling rounds of chemotherapy. The Research prize went to Ludwik Leibler, a Polish-born French materials scientist who invented a class of polymers known as Vitrimers, which can switch from a mouldable consistency to a solid, weldable glassy state; based around combining two types of material which arrange themselves into a supramolecular substance which maintain the number of active bonds at any one time but fluidly rearrange those bonds in an active equilibrium, these materials stay strong while having self-healing properties: readers can expect to read more about vitrimers, which have applications in surgery and restorative medicine, in the coming months.

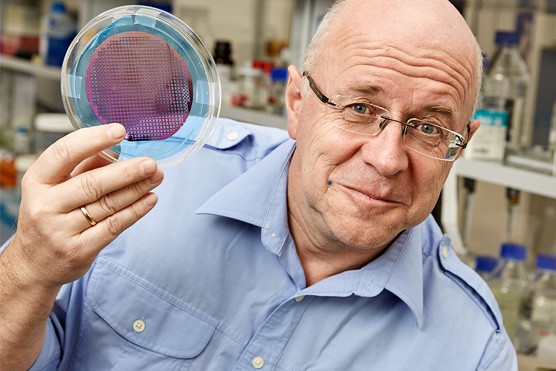

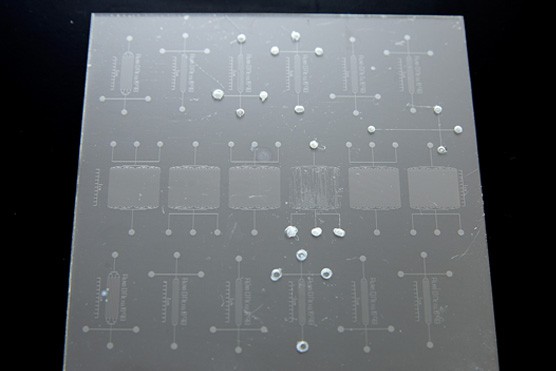

The non-European award went to Japan, with the inventors of carbon nanotubes, Sumio Iijima, Akira Koshio and Masako Yudasaka, seemingly very surprised to be receiving their trophies; and the lifetime achievement award went to Andreas Manz, the enthusiastic inventor of microfluidic lab-on-a-chip devices, who was inspired by a childhood fascination with insects. The public award went to Australian Ian Frazer and the late Chinese professor Jian Zhou, who devised a way to construct virus-like particles out of fragments of brewer’s yeast cells that enabled the invention of a vaccine against human papilloma virus, used to prevent cervical cancer, which has saved the lives of thousands of women: Prof Zhou’s widow, Xiao-Yi Sun, who was also involved with the research, gave a moving speech about her husband’s dedication to solving the difficult problem of developing a vaccine against a highly-unstable virus.

The increasing number of people voting in the public award demonstrates the interest in this award around the world. It seemed a pity that it hadn’t had as much publicity in the UK, a country which has historically prided itself on its inventiveness (if not on its ability to commercialise its inventions). Perhaps Engineer readers can help to change this by nominating inventors for the 2016 award; anyone from industry, a university, research institution, IP association or member of the public can nominate any inventor who has been granted at least one European Patent using this entry form. Don’t be shy.

Poll: Should the UK’s railways be renationalised?

Rail passenger numbers declined from 1.27 million in 1946 to 735,000 in 1994 a fall of 42% over 49 years. In 2019 the last pre-Covid year the number...