For Britain to compete globally in the middle of this century it needs high level engineering skills within a diverse workforce, ready to lead through unprecedented disruption and global competition.

That’s easy to say but the Talent 2050 programme has been set up to put some flesh on the bones of these ideas by listening to the views of engineers around the country and summarising today’s state of play in skills through a review of the many existing research studies, known in the researchers’ trade as a Rapid Evidence Assessment or REA.

We have identified the need for broader skills rather than just technical depth to navigate through change that will include a shift from fossil fuels, new materials for energy storage and the tremendous potential of artificial intelligence and global interconnectivity that will impact far beyond today’s engineering footprint.

We have also identified that this mix of skills will need to come from recruiting a diverse range of people who don’t fit the current maths and physics-dominated profile and particularly emphasise that recruitment of skilled people outside engineering, from other sectors, and supporting them to grow engineering skills whilst in employment, will be needed, a real shift to intersectoral employment from the UK’s current reliance on international recruitment to fill in skills gaps.

It reflects how important engineering skills are to the economy that the project has been created through the National Centre for Universities and Business and has been supported by Barclays Bank, Pearson Education, NATS and London South Bank University.

Rather than duplicate effort, we are also supporting other skills initiatives, including the Independent Commission on Sustainable Learning for Life, Work and a Changing Economy, led by former Education Select Committee Chair Neil Carmichael, which has estimated a massive £108Bn boost to the UK economy through changing skills education.

The workshops were held in Edinburgh, Sunderland and London and included senior individuals from public and private sectors, trades unions, education and professional bodies, early career stage professionals and researchers. They were asked to look at the attraction of engineering careers, barriers to progressing in engineering, missing parts of our current education and skills system, and finally future changes.

FINDINGS

Acknowledging that the supply of STEM and digital skills via schools is not meeting rising demand more focus is needed on retraining staff to encourage intersectoral mobility, transferring skills from different parts of the engineering sector and meeting the challenge of recruiting talent from outside engineering.

A range of contemporary (‘21st Century’) employability skills will also be essential alongside that STEM knowledge. More people with technical qualifications, but unemployable due to a lack of soft skills will not drive the sector forward, nor enable organisations to benefit from technological advances in a globalised economy. ‘Digital literacy’ (and to a lesser extent environmental literacy) is gaining momentum to complement core technical and digital skills of STEM professionals.

Views from the workshops aligned with the themes emerging from the REA, highlighting that known issues are not progressing quickly and meaningfully.

There is slow progress towards the dramatic change that younger participants assumed to be a given. A closer look at the barriers to gaining engineering skills gives a real insight.

Recruitment bottlenecks and barriers

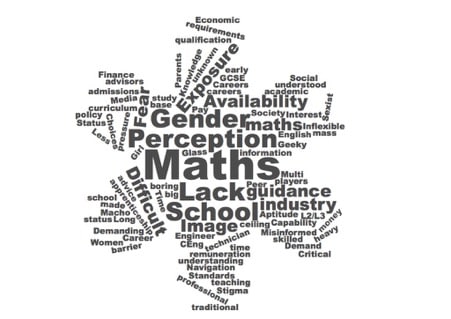

Discussions on the barriers to developing engineering skills proved to be varied but broadly broke down into two categories: societal attitudes and academic requirements. In the word-cloud presentation the dominant word is Maths, in the latter category while perception, gender and guidance are notable societal themes.

The two themes are not wholly independent. A requirement for maths and physics qualifications, for example, to progress into work or further study will immediately shape and limit the pool of applicants whether they are interested in the roles or not, as identified in the REA. It is interesting to note that Chartered Engineer registration was identified as a barrier and further discussion revealed that this was in the context of requirements that were perceived to exclude many and to be too complex.

The group in the North East identified specific barriers to apprenticeships. There was significant concern regarding the requirement for apprentices to achieve Level 2 qualifications in Maths and English by the end point assessment if they had not already attained GCSEs at C or 4 grades when at school.

With current statistics suggesting that three quarters of young people retaking these qualifications will not achieve them by the age of 19 the employers’ concerns are understandable. If employers are unwilling to take on this task, which was the indication here, they would exclude at least 40% of the pool of young people in the North East.

A barrier was also identified in relation to gender, both in the headline term and in terms like “macho” and “sexist”. In the discussion, there was no suggestion that the sector was institutionally sexist but a combination of the historic lack of women in engineering and the recruitment from a male-dominated pool with the desired qualifications already in place could be seen to have that effect.

The Rapid Evidence Assessment notes that changes to qualifications can make this situation worse; the new Computer Science GCSE and A levels have been taken by a cohort which typically already takes maths and physics, is 90% male and predominantly middle class. The 9:1 male female ratio compares unfavourably with 4:1 for A Level Physics which is already considered a failure.

Major change needed

From this initial work some clear themes have arisen. The ‘school to apprenticeship or university’ route for young people, even if changed to more effectively develop the skills outlined here, will not address the necessary change quickly enough. To drive a more diverse workforce and avoid skills shortages engineering needs to reach beyond existing STEM employees and consider a more inclusive approach where recruitment or enrolment is based on the potential to gain the right skills rather which avoids rejecting talented people who haven’t already obtained them.

The Institute for Apprenticeships and Government should reconsider the requirement for employers to take apprentices to Level 2 in English and Maths by the end point assessment, so employers can be actively encouraged to develop young people who display practical talents.

Upskilling and reskilling must be fully supported for those already in work, whether within the sector or bringing complementary skills through intersectoral job mobility. This will need to be regionally tailored and applicable to SMEs as well as major corporations.

Digital skills, including AI, and environmental protection provide the foundation for future change and need to be fully integrated, with regional support, in an industrial strategy that embraces interdisciplinary working.

Next Steps

The first part of this work launches next week at the Hitachi/Daily Telegraph Social Innovation Conference and kicks off a second phase with more in depth workshops looking at how future possibilities will shape our skills needs, both for the engineering sector, and for engineering-type skills across sectors and society. The final report and recommendations of Talent 2050 will be published early in 2019.

Talent 2050: Engineering skills and education for the future

Phase 1 Report By Paul Jackson (Jasia Education Ltd) and Robin Mellors-Bourne (Careers Research Advisory Centre) is published on November 7th and available from the National Centre for Universities and Business www.ncub.co.uk

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...