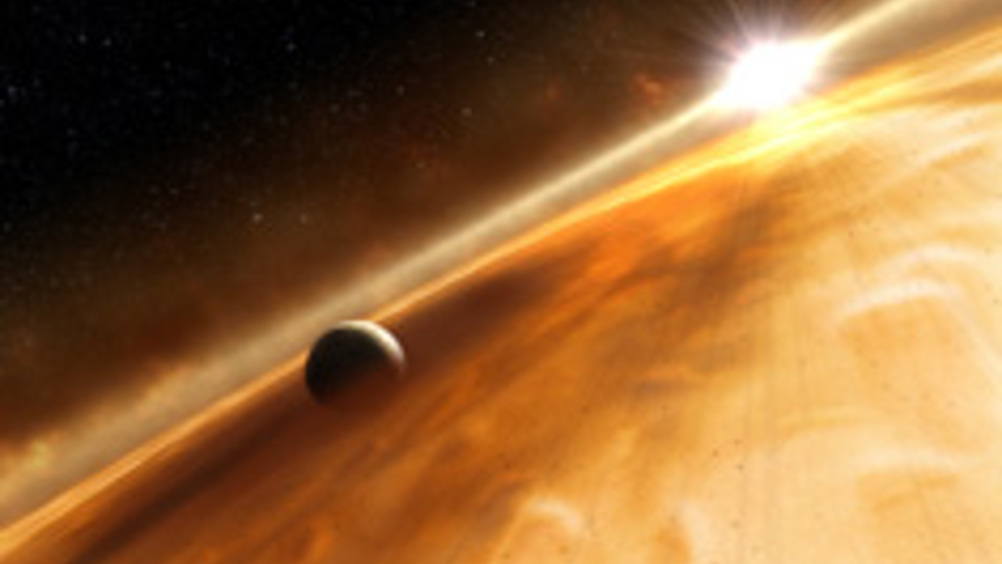

NASA’s scientists have announced one of their most amazing discoveries. Somewhere 2,000 light years away, they have located Earth-sized planets in regions where liquid water and possibly life might exist.

The news broke this week when NASA revealed that its Kepler orbiting space telescope had discovered over 1,200 worlds orbiting distant stars. Of these, around 50 were thought to be similar to Earth, with an ocean and a hospitable atmosphere.

It’s one of those announcements that makes you feel tiny in the universe. As NASA highlights, Kepler’s range covers only 1/400th of the sky and the 50 doppelganger Earths are only a fraction of what could be out there.

Something as momentous as this is bound to reignite long buried ambitions for human space explorations. Those born in the late 50s to early 60s will remember the excitement surrounding the Apollo lunar landings.

Back then, human space exploration had captivated people’s imaginations. The younger generation had lofty ambitions of a successful mission to Mars, the discovery of new planets and maybe even contact with alien life forms.

But it wasn’t to be. The UK, along with the rest of Europe, began moving away from human space flight and towards more profitable space ventures in telecom satellites and robotic probes.

These less glamorous areas are where we’ve excelled. The success of companies such as Surrey Satellite Technology and Astrium, as well as science missions like the Herschel and Planck telescopes, are testament to our engineering skill and ingenuity.

The tactic has payed off economically, but in the longer-term it could have a detrimental effect. Now that human space exploration could be back on the cards, the UK may have to sit back and watch as other countries make their mark.

But should we accept this as our future? And is it really that much of a leap to venture back into human space exploration? According to our latest poll, 57 per cent of you believe that the UK should co-fund the development of a manned space launcher.

Dr David Parker, director of Space Science and Exploration at the UK Space Agency, isn’t so sure. ‘The distinction between robotic and human spaceflight is increasingly blurred,’ he said. ‘Humans can be very efficient explorers of other worlds– on the last Apollo mission, the astronauts travelled 35km in a few days bringing back 50kg of samples.

‘NASA’s Mars rovers have travelled less far in seven years. But they only cost about $1bn compared with the $100bn+ price tag of Apollo (in today’s money): a human Mars mission would cost yet more. So it’s a question of choices…I hope humans will one day go to Mars. But for today, the UK chooses to explore space with robots.’

If, however, the UK did decide to move back into human space exploration it would potentially have knock-on effects for other industries. For instance, the healthcare sector could help provide life support systems and our motor sport industry could get even more involved in advanced material development.

More importantly, UK involvement in human space flight would help capture the imaginations of the country’s future engineers and scientists. Even if the initial cost was high, the payback in terms of wealth generated from an inspired engineering base would be huge.

UK Enters ‘Golden Age of Nuclear’

Apologies if this is a duplicate post - a glitch appears to have removed the first one: > While I welcome the announcement of this project, I note...