As technology journalists, we are frequent visitors to technical conferences and seminars. They tend to be quite similar, even though the range of subjects they cover varies widely. But this week’s event, at the sparkling new Library of Birmingham, had a major difference from all the others I’ve visited: half of the speakers were dead.

The ‘xhumed’ event, which is now touring the country, aims to show how the developments of the industrial revolution are continuing to be felt today as their influence shifts to the digital world. To do this, its organisers have paired presentations from current researchers, writers and others with their equivalents from the 18th and 19th centuries, reanimated in various ways: as projections, voiceovers for films, animations, good old-fashioned portrayals by actors, and in one case, a giant mechanical disembodied mouth.

It’s quite an eerie experience to be addressed by HG Wells, in his own words, as a projection onto the face of a dummy whose physique is far more imposing than the short and slightly tubby Wells, but the author’s prescience about the developments he saw from the early 20th century are somehow even more marked in this format. And it seemed very fitting to hear from some of the members of Birmingham’s Lunar Society, a loose confederation of scientists, industrialists and philosophers who were at the centre of the industrial revolution, in their own city. Mass production pioneer Matthew Boulton, for example, was resurrected in the form of a 3D printed figure, whose production we were talked through, and which then — rather spookily — became an animated figure, addressing the meeting about how the ability of 3D printing files to be transmitted digitally could change the industry which he himself had helped found in the 18th century. I was slightly disappointed that nothing was made of Boulton’s other great contribution to the Industrial Revolution — his business partnership with James Watt, which was instrumental in the development and spread of steam power in industry and later in the railways.

Other presentations were more apposite: the reanimated Joseph Priestley, dissenting clergyman, educator, co-discoverer of oxygen, inventor of fizzy drinks, friend of Revolutionaries and victim of politically-inspired mobs, popped up through the medium of Twitter and attempted to start a ‘Twitterstorm’ by taking against bicycles in cities. Now there’s nothing new about dead people on Twitter. My own Twitter feed includes dead people (Samuel Johnson), fictional people (the nerdily amiable cast of the webcomic Questionable Content by Jeph Jacques) and one dead fictional person (the formidable Leo McGarry of the West Wing) but trying to get a dead person, using their own words from the Library’s archive, to exert real influence on the present is another matter, and I’ll be interested to see how much success @JPriestley1733’s living controller, local author, social media expert and broadcaster Jon Bounds, has in stirring up twitterstorms as the event goes on. Incidentally, he measures the intensity of such storms on a scale named after another Midlander, journalist Caitlin Moran: 0.3Morans is an article on Buzzfeed, 0.5Morans is a column on the Guardian’s website, 0.7Morans is a point-missing, hate-filled diatribe on the Mail Online, and one Moran is a piece on Newsnight. Our efforts this week maybe made a few milliMorans. Could do better (or worse, depending on how you look at it).

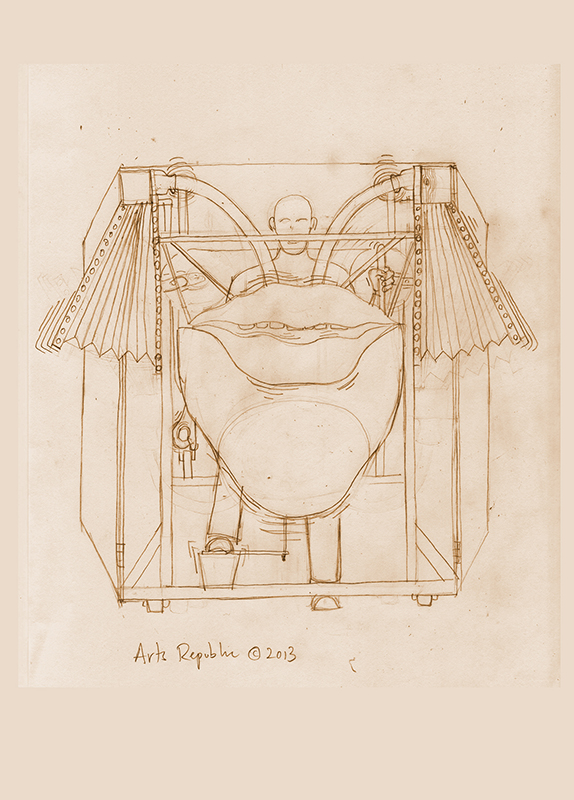

Particularly interesting was a presentation based on the work of another Lunar Society stalwart, physician, poet and natural philosopher Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles). Among Darwin’s many achievements was the invention of a talking machine, with a mouth made of soft leather, vocal chords of stretched silk ribbon, and breath provided by bellows, which he designed to demonstrate the mechanics of speech and his own ideas about how this influenced the development of the alphabet and language. It was a scaled-up version of this — six feet tall and with a mouth about three feet across — which accompanied a voiceover in Darwin’s own words, although it wasn’t readily apparent whether the machine was speaking ‘live’.

This ‘talk’ was acccompanied by a presentation from Christophe Veaux of Edinburgh University, who put Darwin’s work into the context of the development of speech synthesis and brought us up to date with his own work on reconstructing the voices of those who have lost their own, due to neurological disorders such as motor neurone disease or stroke, cancer or injury to the vocal tract. Perhaps the most successful part of the event, this introduced me to the concept of ‘voice donation’, an essential facet of voice reconstruction when the patient has already suffered voice damage when diagnosed — something very common in the case of MND. It’s something I’ll be looking into myself, especially as voice loss has affected my own family, and perhaps gave the clearest demonstration of direct descent of thought and technology from the Industrial Revolutionaries to the present day.

Slightly less relevant from an engineering point of view, but still interesting, were talks on the value of voluntary work, from the late Geraldine Cadbury, one of the first female magisrates and a pioneer in the treatment of juveniles in the Criminal Justice System, and Helen Milner, CEO of the Tinder Foundation, which helps the elderly and disengaged to access the resources of the internet; and a distinctly disturbing address from the shade of outspoken atheist John Baskerville, who against his clearly-stated wishes was exhumed, exhibited and reburied three times, accompanied by a talk about the digital and physical rights of the dead by John Troyer of the sepruchally-named Centre for Death and Society of the University of Bath. Inevitably, that spectre of scientific progress, Victor Frankenstein and his monstrous creation, reared their ugly heads, via a presentation from their own creator, Mary Shelley, whose image was effectively mixed with that of the False Maria robot from Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis, and a talk from science writer Jon Turney, touching on the convergence of machine and human memory. This last struck a slightly false note for me: although Shelley must have been irresistible to the organisers, she was influenced much more by scientists like Faraday and Davy than by industrialists. Maybe early cosmologist Catherine Herschel or utopian writer and scientist Margaret Cavendish might have been a better match.

Overall, it was a memorable, entertaining and informative afternoon, which is probably the most you can wish for, but I was left wondering exactly who the event was intended to address. If it’s younger people, it needs better introductions; I’m the sort of dull person who knows who Erasmus Darwin et al were, but it’s not exactly common knowledge. But it certainly helped to increase the impact of the contemporary speakers. Maybe we should consider an address by the late IK Brunel or George Stephenson — or Messrs Boulton and Watt — at the next Engineer Conference.

Nanogenerator consumes CO2 to generate electricity

Nice to see my my views being backed up by no less a figure than Sabine Hossenfelder https://youtu.be/QoJzs4fA4fo