Stuart Nathan

Stuart Nathan

Features editor

A new BBC programme may have found the ideal formula to make engineering attractive

Regular readers might remember that I keep a keen eye on media portrayals of engineering and technology, both fictional and real. In general, I prefer to praise those who get it right rather than criticise those who get it wrong; and I'm delighted to say that the BBC programme Big Life Fix with Simon Reeve gets it right to a degree that I think may be almost unprecedented.

Two editions of the programme have already been transmitted with the third and final instalment screened tonight at 9 PM on BBC2. With my usual highly scientific method of gauging reaction to such things (asking friends, family and colleagues) it appears that the series has escaped the notice of many; so if any readers have also missed it, the premise of the series is as follows. The programme makers have assembled a team of seven engineers, referred to variously as "makers", "inventors" and simply "experts", who in each episode are presented with three problems facing individuals or communities, and tasked with coming up with a technological solution which they then build and present to their "clients".

So far in the series, we have seen the team tackle the problems of four people facing physical disability of some sort; a young man named James Dunn who suffers from a skin condition caused by collagen deficiency which causes him intense pain and has fused his fingers together, preventing him from using his camera, a vital creative outlet and source of distraction from his condition; Emma Lawton, a designer with Parkinson's disease which was preventing her from drawing or writing; Oscar Johnson, a teenage boy born with no hands or feet, who dearly wanted to be able to ride a bike to spend time with his friends; and Graham, who has been robbed of his speech and much of his movement by a severe stroke and struggles to communicate with his wife and family.

Two other projects involve communities; one, the remote village of Staylittle in Wales, where communication is hampered by appalling phone reception and almost non-existent Internet; the other, a group of farmers in Yorkshire who are plagued by sheep rustling.

The series is notable for the accurate way in which it portrays engineering projects. We see the experts going to visit the "participants", as the production company called them, receiving a detailed briefing and asking questions, then returning to their base (a "maker space" in Bethnal Green) and discussing the problem among the team who bring the different skills to bear.

We are talked through how the project leader comes up with ideas for the solution, shown the initial prototype phase and its presentation to the participant, shown how more often than not this phase does not work; taken back to base for a rethink and rebuild, and then shown the final result and the participant’s reaction.

During this process, we get to know the team a little; they are a notably diverse bunch, mostly young (mid 30s in general), with both male and female participants and from a variety of backgrounds. They include an industrial designer, an electronics specialist, a materials scientist, a design strategist and others who all bring their unique viewpoints to bear on their projects.

Series producer-director Tom Watt-Smith, from production company Studio Lambert, which produced Big Life Fix for the BBC, told The Engineer that this dual focus was deliberate. "We always wanted to tell these two stories in parallel: the fixers and the participants," he said in a phone conversation. "And it was important to show how they worked, the tools they used and the way they bounce ideas off each other."

This has the welcome effect of humanising the participants; at no point do they seem remote or disconnected, and we are also shown that they have lives outside their work (two of them had new babies at the time the series is being shot, and we see and hear them in sequences with the team). We are also told how the team’s backgrounds influence their thinking; for example, two of the fixers working on the sheep rusting project came from rural communities and were used to being on farms, while the project leader building Oscar's bike was an enthusiastic cyclist himself.

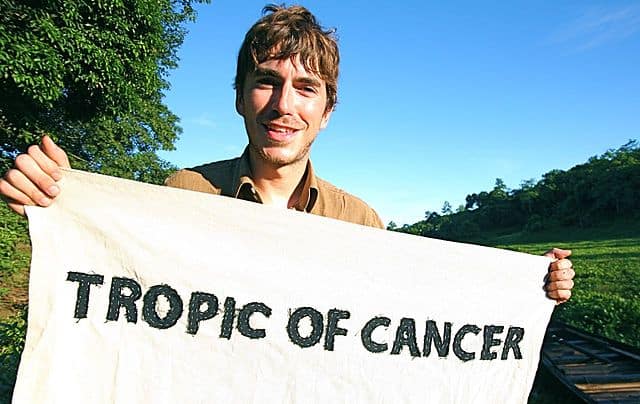

The choice of presenter Simon Reeve, best known for travel documentaries and without a technical background himself, was taken so that viewers had an easily relatable guide to what was going on. "We thought that as we had these seven brilliant people, it was important to have somebody talking to them on the viewers’ level," Watt-Smith explained. And Reeve does a good job, explaining complex concepts like how 3D printing works and current theories about the neurological causes of Parkinson's disease.

It's also oddly heartening to see the series insistence on showing us the difficulty of persuading the participants to go along with the team's ideas, and the inevitable failure of early prototypes. "We had to get that in," Watt-Smith said. "The team insisted, and it is such a vital part of how the project develops."

The final reveal of the project results is an inevitably moving sequence; Emma being presented with a custom wristband containing vibrating motors that distracted her motor system from tremors and allowed her to write her name and draw a straight line freehand for the first time in six years was a tearjerker, as was Graham using a touchscreen pad triggering samples of his own voice (gleaned from long forgotten home videos) and hilariously profane samples from television shows to communicate with his wife. James's camera, equipped with a motorised system to control zoom and focus, linked to his wheelchair battery and controlled via tablet app which did not need him to drag his fingers across the screen was another sublime television moment.

"We are considering showing fewer projects per episode in the next series," Watt-Smith said. "We have to cut such a lot out, and it might be good to let the stories breathe a little." The format of three stories per episode was formulated to allow some time away from the medical oriented projects, which the team affords were rather intense to watch, but were chosen for the focus of the project because they are easy to relate to and emotionally involving for viewers and participants.

It was noticeable (to me, at least) that the team is sparing with the terms engineer and engineering, but Watt-Smith told me this was not deliberate. "we asked the team how they would like us to describe them," he said. "There certainly wasn't a feeling that engineering wasn't sexy enough for us to talk about."

What struck me immediately was that a young person watching the series might instantly think "that looks really cool, I want to do that." This was borne out watching Channel 4’s people-watching-TV series Gogglebox, where one of the younger participants commented "that must be the best job in the world, coming up with ideas and helping people like that."

Watt-Smith was open to the idea of producing information packs for teachers to accompany subsequent series, so they can advise any students thinking likewise on how they can find out more about engineering and training. In the meantime, the BBC's webpage for the series has links to online resources.

Unfortunately, most of the daily newspapers have ignored the programme. Some of the fixes have made it onto the news pages, but the only review I have seen depressingly focused on whether the team had "mad inventor hair". For the record, only two of them do, and that's a stretch for one of those. But how depressing that the instinct of the reviewer (let's name and shame, it was in the Daily Telegraph) was to stereotype rather than to look at the team's achievement.

I would urge any readers to catch the final instalment of the show tonight, and to keep an eye out for its return, which has been confirmed by the BBC.

IEA report claims batteries are ‘changing the game’

Batteries come with major weight penalties in vehicles and to date have only achieved very limited application in the rail sector where range and...