The aerospace defence sector is often regarded as the jewel in the crown of the UK’s engineering sector. It’s the repository of the most advanced skills, the generator of the biggest and most lucrative (if also the most controversial) exports, the target of the most cutting-edge research. It’s the flagship of Britain’s competitiveness as well as embodying many of the traditions of ingenuity, innovation and sheer bloody-minded eccentricity of the country’s engineering heritage, from the development of the Spitfire to the jet engine and on to the Lightning and the Harrier.

It’s also an industry that’s seen as being healthy, often named by politicians as a model for the rest of the manufacturing sector. But, according to a discussion paper from the Royal Aeronautical Society (of which you can read a summary here), this is an industry in danger.

Arising from a conference held last year, the discussion paper points out the changes in the industry over the past few decades. As the complexity of military aircraft has grown, so it has become increasingly difficult for single nations to shoulder the cost of developing them. The major aircraft development programmes in the UK are now part of international collaborations — the Typhoon and Airbus A400M with other European nations, the F35 Lightning II with the US as the major partner — and each country contributes according to its investment in the programme. Nobody can do everything; and that, the RAeS says, means that valuable skills in the UK are in danger of stagnating.

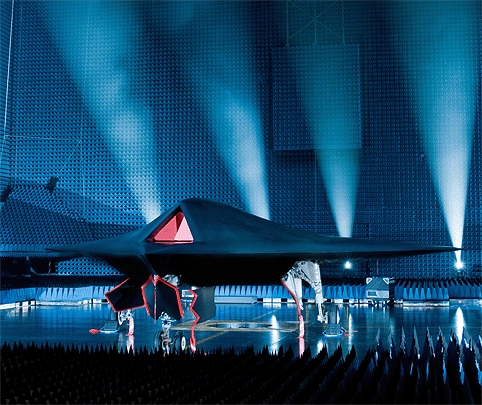

The Society is calling for a debate on the future of the industry, asking the government to recognise that, valuable though they are, the technology of UAVs and the production of overseas-designed equipment will not be enough to generate the IP and safeguard the skills that the UK will need to keep its aerospace defence industry at the international forefront. We need to make sure that we have the skills and expertise in airframes, avionics, propulsion, system integration and sensors to cover the entire development and manufacturing process, it says; this could be achieved by varying the roles UK companies take on in collaborational projects, and leaning more towards European collaborations than American, as these have greater technological benefits and more chance of retaining the crucial intellectual property.

It’s a subject that we’ve covered in The Engineer before. If nobody designs and builds a plane from scratch anymore, how do you ensure that we have all the skills to do it? And it has to be said, the attitude we’ve encountered occasionally when visiting aerospace companies does chime in with the RAeS’s concern. I’ve been told that, although we don’t build whole Airbus airliners in the UK, ‘we build the most important and most interesting bit’ (ie, the wings) and that should be sufficient. I’ve also heard, as the airworthiness rules for a UAV are the same as for a manned aircraft, developing UAVs in the UK is sufficient to maintain skills and safeguard what’s known in the defence industry as ‘sovereignty’ — the ability of the country to manufacture what it needs to defend itself — without having to worry about developing and building a fighter aircraft, for example, single-handed.

This is an extremely complicated argument with many aspects. If the reality of the aerospace industry is that no single company or country develops a military aircraft, does it matter if each country doesn’t have all the skills to develop it alone? Moreover, it now takes so long to develop an aircraft that an engineer can spend his or her entire career on a single project without seeing it fly or without being there at the conceptual design stage — how then do you ensure that the entire spread of skills is fostered? Indeed, this is an aspect which is recognised in the UK: Cranfield University, for example, runs a master’s course specifically designed to give students the experience of seeing through an aircraft development programme from conception to test-flight.

The complexity of the question means that the RAeS is undoubtedly correct: there needs to be a debate on this. Maybe opening up the innovation path, bringing in expertise from other sectors such as motorsport, space and the process sectors, can help maintain skills in aerodynamics, systems integration, fluid dynamics and sensors. Maybe, in the wake of its aborted merger with Airbus, BAE Systems needs to investigate setting up its own civil aircraft development programme, which could feed skills into its parallel military aircraft division. It needs a long-term view and some futurism, which is always a tricky business. But the UK needs to be a player in the skies for all sorts of reasons, and the future of the aerospace industry should not be left to drift.

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Well let´s do a little experiment. My last (10.4.25) half-yearly water/waste water bill from Severn Trent was £98.29. How much does not-for-profit Dŵr...