According to the team the system is able to generate enough power to run small sensors or drug delivery devices for extended periods of time, and could lead to novel ways of monitoring patient health and treating disease.

Ingestible medical devices are usually powered by small batteries, but these self-discharge over time and can pose safety risks for patients.

In an effort to develop an alternative approach the team took their initial inspiration from the so-called lemon battery, a simple voltaic cell consisting of two electrodes stuck in a lemon. The citric acid in the lemon carries a small electric current between the two electrodes.

To replicate that strategy, the researchers attached zinc and copper electrodes to the surface of their ingestible sensor. The zinc emits ions into the acid in the stomach to power the voltaic circuit, generating enough energy to power a commercial temperature sensor and a 900-megahertz transmitter.

In tests in pigs, the devices took an average of six days to travel through the digestive tract. While in the stomach, the voltaic cell produced enough energy to power a temperature sensor and to wirelessly transmit the data to a base station located 2 meters away, with a signal sent every 12 seconds.

Once the device moved into the small intestine, which is less acidic than the stomach, the cell generated only about 1/100 of what it produced in the stomach.

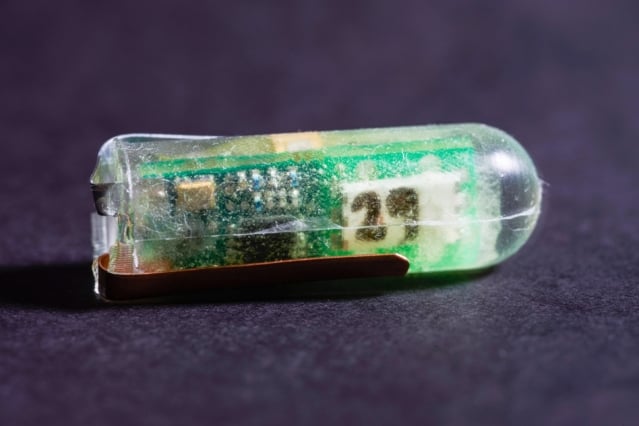

The current prototype of the device is a cylinder about 40 millimetres long and 12 millimetres in diameter, but the researchers anticipate that they could make the capsule about one-third that size by building a customised integrated circuit that would carry the energy harvester, transmitter, and a small microprocessor.

Once the researchers miniaturise the device, they anticipate adding other types of sensors and developing it for applications such as long-term monitoring of vital signs. “You could have a self-powered pill that would monitor your vital signs from inside for a couple of weeks, and you don’t even have to think about it. It just sits there making measurements and transmitting them to your phone,” said MIT postdoc Phillip Nadeau, lead author of a paper on the work, which appears in the Feb. 6 issue of Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Nanogenerator consumes CO2 to generate electricity

Nice to see my my views being backed up by no less a figure than Sabine Hossenfelder https://youtu.be/QoJzs4fA4fo