Personalised heart simulations could improve cardiac care

UK developed technology that simulates the workings of individual patients' hearts could boost treatment of a common cardiac condition that affects a million people in the UK, researchers have claimed.

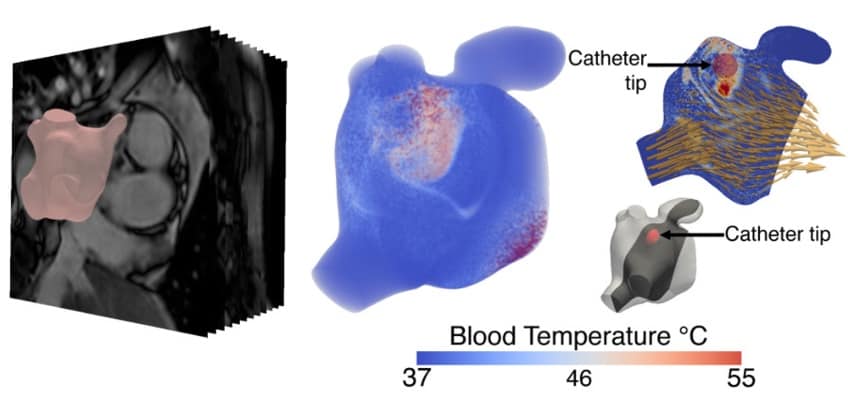

Working with £93,000 funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) the team at King's College London has taken the first steps towards developing models designed to optimise catheter ablation, a procedure used to correct atrial fibrillation, a condition which causes abnormal heart rhythms.

Atrial fibrillation - which affects the left atrium (or upper chamber) of the heart - reduces blood supply, leading to dizziness, breathlessness and fatigue, and increases the risk of a stroke. Every year, around 10,000 people in the UK have a catheter inserted in order to treat the condition using radiofrequency energy. But the procedure is not always effective, there is a small risk of it causing a stroke or death, and the condition often recurs.

The personalised computer models aim to increase the effectiveness of this procedure by making it possible to explore, in advance, different strategies for its use geared to the specific needs of individual patients.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...