Researchers go for gold in rapid test for influenza

Researchers have developed a rapid test for influenza by coupling antibodies with gold nanoparticles and measuring the light-scattering properties of the resulting complex.

Arriving at a rapid and accurate diagnosis is critical during flu outbreaks, but, until now, public health officials have had to choose between a highly accurate yet time-consuming test or a rapid but error-prone test.

‘We’ve known for a long time that you can use antibodies to capture viruses and that nanoparticles have different traits based on their size,’ said Ralph Tripp of University of Georgia, who led the team that developed the new technology. ‘What we’ve done is combine the two to create a diagnostic test that is rapid and highly sensitive.’

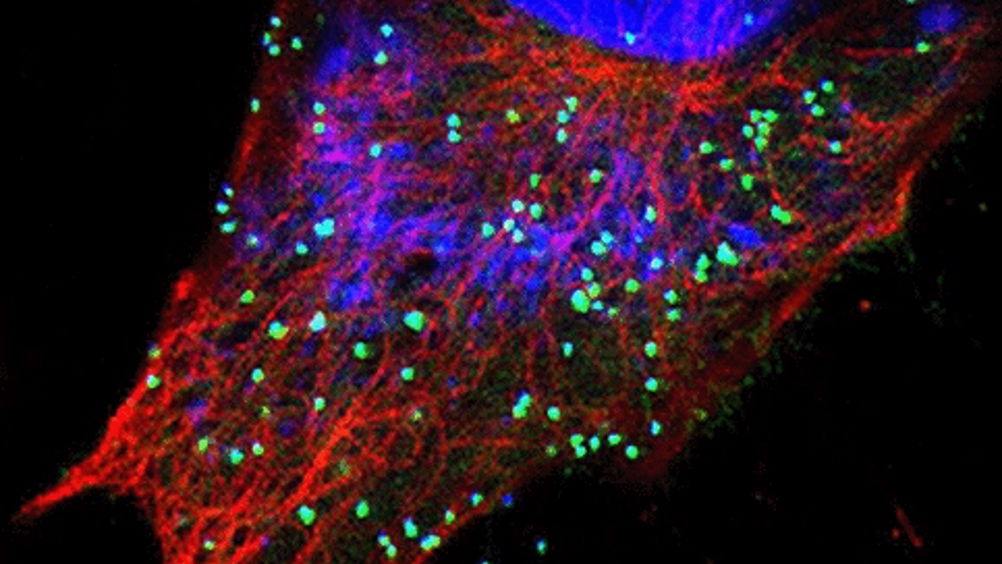

The team coated gold nanoparticles with antibodies that bind to specific strains of the flu virus and then measured how the particles scatter laser light.

The gold nanoparticle-antibody complex aggregates with any virus present in a sample and a commercially available device measures the intensity with which the solution scatters light. The clustering of the virus with the gold nanoparticles causes the scattered light to fluctuate in a predictable and measurable pattern.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...