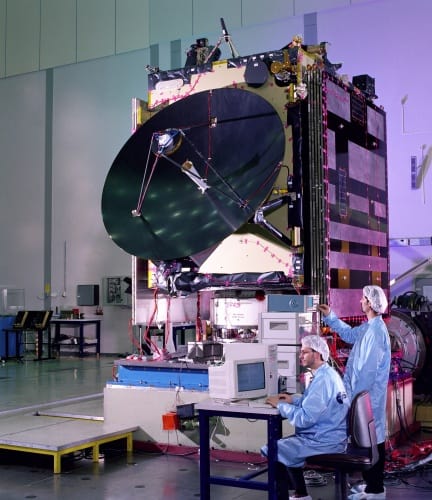

As I write this, a chunk of metal and carbon fibre about the size of a double wardrobe is in orbit around a comet 400 million miles from Earth.

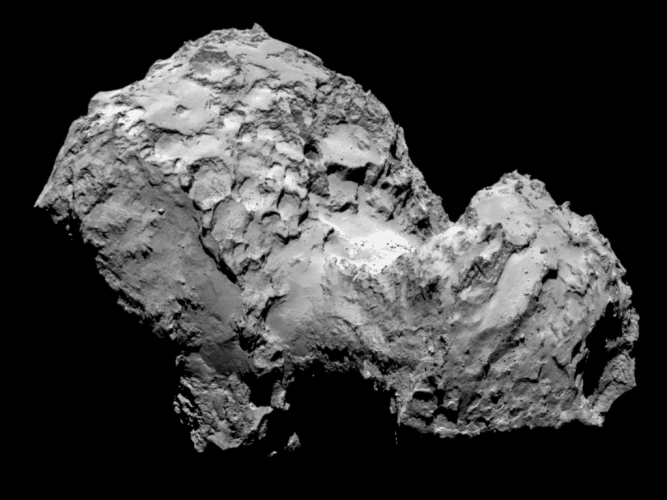

Packed with electronics and analysis equipment, the Rosetta probe was launched ten years ago with the ambitious goal of intercepting a comet to investigate its composition — a deep-frozen sample of the solar system as it was during its formation, 4.6 billion years ago. But what seemed like a far-fetched notion back in the ’90s is now happening: after three orbits around Earth, one around Mars and a slingshot around Jupiter, during which it was in electronic hibernation, Rosetta is now on-station at Comet 67P Churymov-Gerasimenko and ready for the next part of the mission: to send a lander, called Philae, in to land on the comet itself in November.

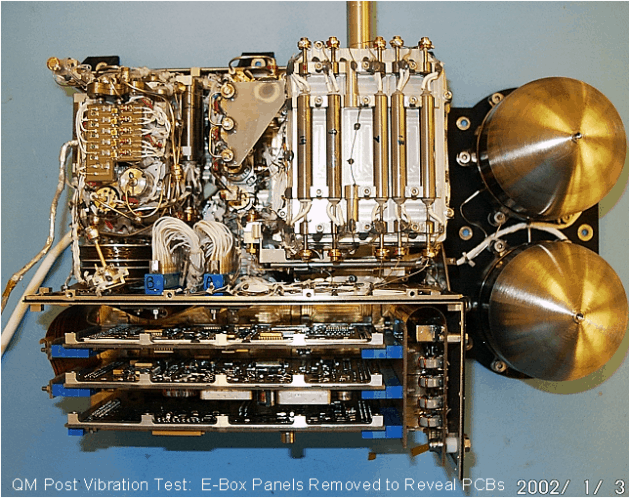

As well as being a mindboggling achievement of engineering in itself, Rosetta and Philae are an effective riposte to those who believe that space exploration missions such as these are a scientific indulgence and of no practical use on Earth for among Philae’s instruments is a mobile laboratory called Ptolemy. Built by the Open University and the Rutherford-Appleton Laboratory’s Space division with EPSRC and Wellcome Trust funding, Ptolemy is about as big as a shoebox and uses as much power as an incandescent lightbulb. Within that small space, Ptolemy contains miniature ovens, valves, a supply of helium and a mass spectrometer and analysis equipment. Once on the comet surface, Ptolemy will test a few grains of the icy matter of the comet and determine, with great accuracy, the isotopes which make up the sample. For planetary scientists, this will provide evidence of how the solar system formed: evidence which can’t be gathered any other way because the distant trajectory of the comet in deep space has preserved its composition; tectonics and erosion removed this material from planets aeons ago. But it’s also of direct benefit on Earth; and could save lives.

To withstand the rigours of deep space, Ptolemy had to be made simple and robust. More than ten years on from its manufacture, its technology is now being used to develop breath tests to detect stomach ulcers, which are caused by an infection that has been linked to cancer; the techniques it uses are being adapted to detect and monitor bed bug infestations.

When Ptolemy was developed, it was thought that its simplicity and sensitivity could be used to detect telltale chemicals that indicate tuberculosis infection, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where rapid, accurate tests are badly needed. Although successful trials were carried out, lead researcher Geraint ‘Taff’ Thomas of the Open University tells The Engineer that it has since been superceded by a DNA-based test developed by US firm Cepheid. Thomas, who now is a director of two start-up companies based on Ptolemy technologies at the ESA Business Incubation Centre at Harwell developing the tests detailed above, tells us he intends to return to the diagnostic potential of GC-MS in the future.

The same technology is also to be used by BAE Systems aboard its next generation of submarines, the proposed replacement for Trident. Employed to sample the atmosphere on the submarines, the detectors will be able to measure three times as many gases with better accuracy than existing systems, and at a lower price.

None of these applications were invisaged by the team at the start of the project, which demonstrates that the exacting standards of space engineering are a fertile breeding ground for useful technologies, even when they aren’t obvious. So next time you’re tempted to think ‘Why are they spending our tax money on that?’ when you see an article about some esoteric space mission, think about Rosetta and its life-saving payload.

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...