1. Make sure you’re ready to recruit

It is vital that an organisation understands the strengths and weaknesses of its talent pool and how this changes over time. Without a process in place to audit the existing knowledge and skills base, a business is in danger of recruiting for the wrong role or being too knee-jerk in its approach. This should always be the first step of the recruitment process before a job specification is even considered.

2. Offer a career path, not a job

When the candidate has the upper hand they want to know about the long term prospects a role offers. In developing the job specification, paint a picture of the prospective career path to capture the attention of candidates and ensure it is a central part of the interview. Even if there is an immediate and urgent need to fill a role, good candidates will be put off by the slightest hint of short term thinking from the employer.

3. Sell your organisation

The interview is a two-way process, particularly when good candidates are in such high demand. Engineering firms need to think about how they are perceived externally and what information they need to share with prospective employees to convince them to join their organisation. Trust candidates by sharing plans for growth and details of innovative projects that showcase the credentials of your organisation. This is especially important for SMEs who do not have the kudos of major brands.

4. Think global

The international nature of the engineering labour market presents an opportunity for UK employers. Those who haven’t already should consider applying for a sponsor licence, which will enable a company to recruit from outside the EEA in circumstances where there are no available candidates.

5. Consider transferable skills

Employers usually want a candidate with sector experience - by its nature the engineering industry has always taken this specialist approach, but there is definitely a crossover between sectors that employers could use to their advantage more frequently. For example, the automotive and FMCG sector share the same fast-paced, customer oriented environment and a highly skilled engineer with an automotive background could offer an adaptable and valuable skill set to an FMCG organisation with some support and training.

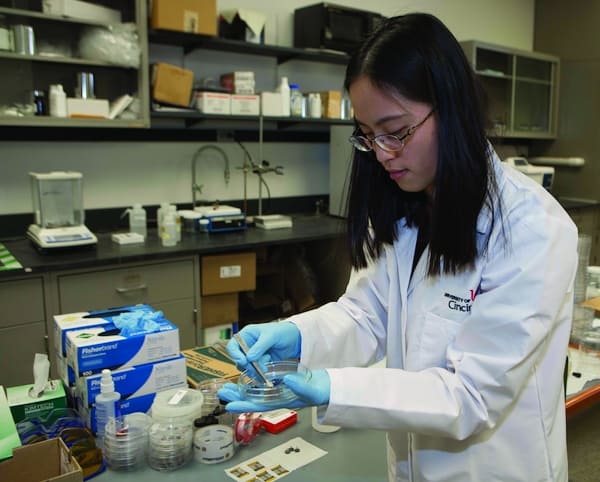

6. Invest in tomorrow’s engineers

Unfortunately there is no quick fix to the skills shortage, but if businesses want to reverse the trend of a declining talent pool they have to be prepared to invest in training. Supporting young engineers through their training - either via apprenticeships or university - is essential to ensuring today’s problem doesn’t derail the long term health of the engineering sector.

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...