The Engineer has a detailed archive of stories serving up a rich seam of fascinating content from engineering’s past. One of the most interesting veins is The Engineer’s investigation of some of the key technologies that helped win the Second World War for the Allied forces. The conflict marked a new stage in the mechanisation of warfare, which meant that engineers and their inventions were critical factors in the eventual Allied victory.

Merlin powers the Spitfire fighter to new heights

The Engineer was invited by Rolls-Royce Ltd in December 1942 to inspect an example of the firm’s new Merlin 61 supercharged aero-engine, which was being fitted by the RAF to an improved Spitfire then operating with Fighter Command.

The article was able to position such a development as part of a continuous wartime process. It recalled that at the beginning of the war and during the Battle of Britain, every RAF first-line fighter was fitted with the previously mentioned Merlin III engine, and, striking a more patriotic note, “the complete defeat of the Luftwaffe in August and September 1940 definitely established the technical superiority of British machines. The superiority was not obtained by chance, but every move of the enemy had been anticipated and a definite counter-move worked out”.

Learn more about Rolls-Royce’s Merlin engine and the Spitfire fighter

Dunkirk ‘Little Ships’ aid an armour revolution

The ‘Little Ships’, crewed mainly by Royal Navy reservists, formed a significant part of what wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill described as the “miracle of deliverance” at Dunkirk. Among the Little Ships’ crews, however, observations had been made that would lead to the development of a material that, towards the end of the Second World War, would save thousands of lives and tons of steel. The material was plastic armour and, in August 1945, Dr JP Lawrie of the Royal Naval Scientific Service penned an article for The Engineer that summarised the material’s development and its quick evolution for use during the D-Day landings of 1944.

Discover more about the development of plastic armour

The first flight of the Lancaster bomber

By August 1942 when The Engineer was invited to see it in action, the Lancaster had already started to make a name for itself in the Second World War. “But a few months after its completion, the ‘Lancaster’ has left its mark on the German landscape and its people,” wrote our predecessors. “It has helped powerfully by night to batter Cologne and Essen, with bombs of the heaviest calibre. By day it carried out the epic raid led by squadron leader JD Nettleton, VC on Augsburg, and the raids on Danzig and Flensburg. From the initial flights and the report of the Ministry of Aircraft Production testing staff, it was soon obvious that the Allied cause had now what has since been aptly styled by many pilots as a ‘war winner’.”

Read more about the first flight of the Lancaster bomber

The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The Engineer is a conduit through which technological advances are communicated and, in doing so, it has documented periods in mankind’s history that are horrific and awe inspiring in equal measure. This point was brought to bear in January 1946 whenThe Engineer reported on the use of atomic weapons against Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the Second World War. Specifically, 5 August 1945 saw the US drop a 15kt atomic bomb on Hiroshima that wiped out over four square miles of the city, which was around 60 per cent of its total area. Four days later, a second, more-advanced, 21kt bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, which was afforded a degree of relative protection by its mountainous geographical features.

Read more about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

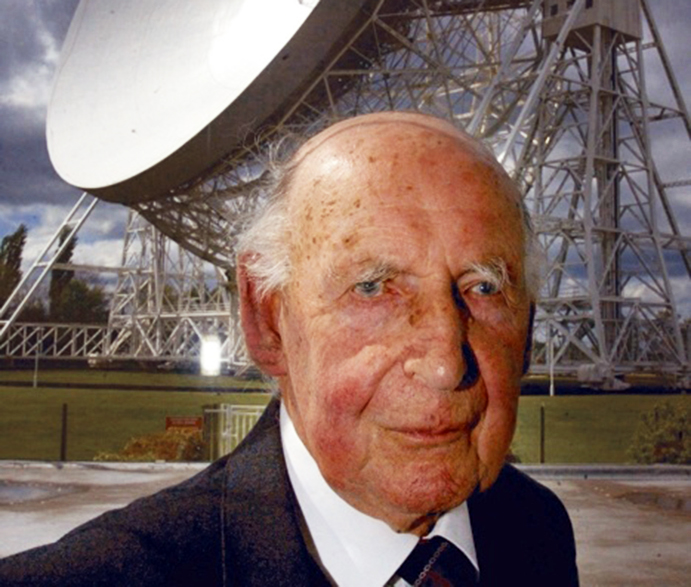

Pioneer of radar – Sir Bernard Lovell

Following the Battle of Britain in September 1940, British Bomber Command had increased the number of night time raids on German cities, but reconnaissance was indicating that many of these bombs were falling on open country. So, at the beginning of 1942, Bernard Lovell, who had spent the last couple of years developing short wavelength air interception radar and blind firing systems for fighter planes, was told to form a group to develop a blind bombing system. Based at the government’s Telecommunications Research Establishment in the Dorset clifftop village of Worth Matravers, he set to work on the development of a precision bombing device that would use a rotating antenna within a cupola attached to the belly of a bomber to build up a map of the terrain below.

Learn more about eminent astronomer and pioneer of radar Sir Bernard Lovell

The Post Office Research Station and the Colossus code-breaking computer

The Colossi computers were developed for British code breakers in 1943-1945 to help in the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz German rotor stream cipher machines used by the German Army during the Second World War. Colossi used thermionic valves (vacuum tubes) and thyratrons to perform Boolean and counting operations. Colossus has thus been regarded as the world’s first programmable, electronic digital computer, although it was programmed by plugs and switches and not by a stored program. The Colossus was the product of the British Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill in north-west London and opened in 1933, responsible for a host of technological breakthroughs. Reporting on its grand opening in 1933,The Engineer wrote that “it is doubtful… if a more elaborate or better equipped establishment devoted to electrical communication investigations can be found”.

Learn more about the Post Office Research Station and the Colossus

Poll: Should the UK’s railways be renationalised?

Rail passenger numbers declined from 1.27 million in 1946 to 735,000 in 1994 a fall of 42% over 49 years. In 2019 the last pre-Covid year the number...