As the industrialised world’s first Metropolis, London has been from surprisingly early in its history a vertical city. Towers and spires have been its hallmark for many years, and although the skyscraper trend passed London by as it raised the height of American cities early in the 20th century, it has since caught up.

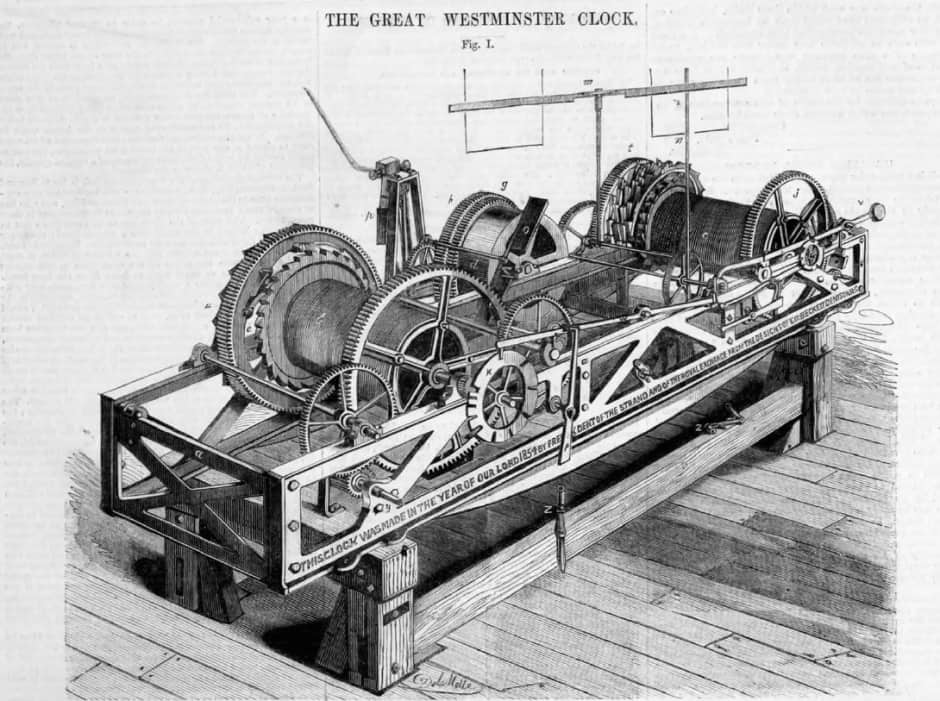

1856 Westminster clock

Not a tower as such but the focal point of the best-known towers in the world, the clock of the Houses of Parliament – universally known as Big Ben, although it is equally well-known that the name strictly speaking applies to its bell – is a feat of engineering in its own right. We wrote about the clock, towards the beginning of The Engineer’s existence in 1856, and nine years later featured the obituary of its formidable designer, the horologist Edmund Beckett Denison, Baron Grimthorpe.

REVISIT THE ENGINEER'S ARCHIVE HERE

AND READ ABOUT BARON GRIMTHORPE HERE

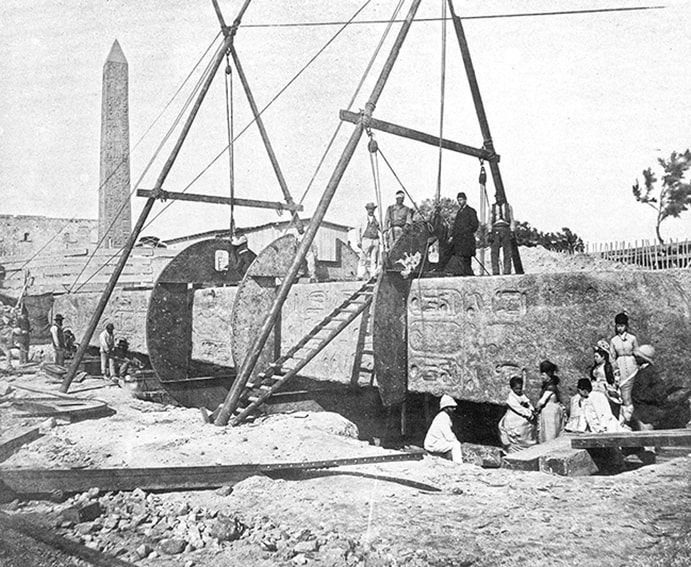

1878 Cleopatra’s needle

The oldest structure in London by several centuries, the Egyptian obelisk known as Cleopatra’s Needle was a gift from the government of its home country. Transporting it from the Middle East, across the Mediterranean to its new home by the Thames was an epic undertaking, whose many twists and misfortunes were covered back in 1878.

REVISIT THE ENGINEER'S ARCHIVE HERE

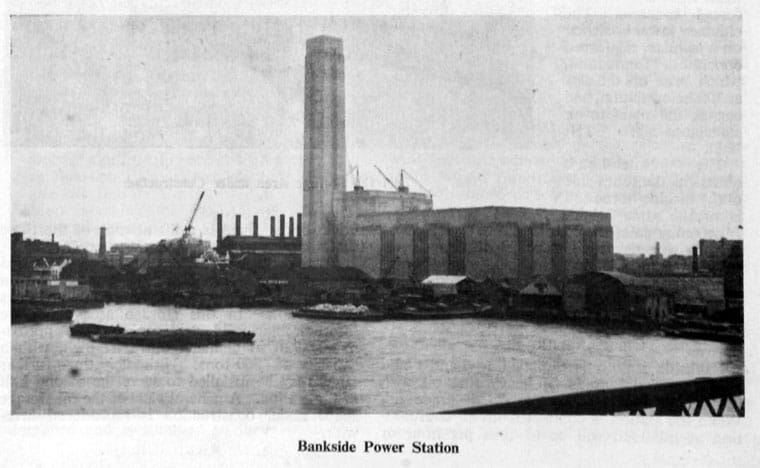

1899 Bankside Power Station

Occupying what might be one of the world’s top pieces of real estate, directly opposite St Pauls Cathedral, the massive brick edifice of Bankside Power Station was among the first landmarks of the age of electricity near the turn of the 19th century. Now occupied by the modern art collection of the Tate Gallery, its towering chimney no longer belches smoke but acts as the vantage point for art lovers willing to take a journey in its lift. Before its conversion, it was unloved and unoccupied for many years, towards the end of which period it stood in for the Tower of London in Sir Ian McKellen’s filmed production of Richard the Third.

REVISIT THE ENGINEER'S ARCHIVE HERE:

1961 Telecom Tower

Our near neighbour in the relatively diminutive Engineer Towers, Telecom Tower (previously known as the Post Office Tower, and before that the GPO Tower) was a paradox for many years: according to the Official Secrets Act, it didn’t actually exist, although could be seen clearly dominating the skyline of the West End of London, featured on the logo of Thames television and played a memorable role in the comedy series The Goodies when it was demolished by a giant-sized fluffy white kitten. Housing transmission equipment for the UK’s telephone system, the tower was built in the “white heat of technology” period just before the 60s started to swing, and despite the secrecy The Engineer was there to cover it.

REVISIT THE ENGINEER'S ARCHIVE HERE:

2005 The Shard

The highest recent addition to London’s skyline, Renzo Piano’s skyscraper The Shard is the tallest building in Europe, looming over the urban architecture south of the river near London Bridge. The unhelpful geology of the locality necessitated the use of some innovative construction techniques to help the slender pointed tower rise to the heights. The designer of the Shard’s peak, structural engineer Roma Agrawal, contributed a blog article to The Engineer just short of the tower’s 10th birthday.

READ THE ORIGINAL FEATURE HERE:

AND READ ABOUT ROMA'S 'SIX YEARS OF FUN' WORKING ON THE SHARD HERE:

Labour pledge to tackle four key barriers in UK energy transition

I'm all for clarity and would welcome anyone who can enlighten me about what Labour's plans are for the size and scale of this Great British Energy....