The Rice lab of materials scientist Jun Lou created the new cathode, one of the two electrodes in batteries, from nanotubes that are seamlessly bonded to graphene and replaces the expensive and brittle platinum-based materials often used in earlier versions.

The discovery was reported online in the Journal of Materials Chemistry A.

Dye-sensitised solar cells have been in development since 1988 and employ cheap organic dyes that cover conductive titanium dioxide particles. The dyes absorb photons and produce electrons that flow out of the cell for use; a return line completes the circuit to the cathode that combines with an iodine-based electrolyte to refresh the dye.

While they are not as efficient as silicon-based solar cells in collecting sunlight and transforming it into electricity, dye-sensitised solar cells have advantages for many applications, said co-lead author Pei Dong, a postdoctoral researcher in Lou’s lab.

‘The first is that they’re low-cost, because they can be fabricated in a normal area,’ Dong said in a statement. ‘There’s no need for a clean room. They’re semi-transparent, so they can be applied to glass, and they can be used in dim light; they will even work on a cloudy day. Or indoors. One company commercialising dye-sensitised cells is embedding them in computer keyboards and mice so you never have to install batteries. Normal room light is sufficient to keep them alive.’

The breakthrough is said to extend a stream of nanotechnology research at Rice that began with chemist Robert Hauge’s 2009 invention of a so-called ‘flying carpet’ technique to grow very long bundles of aligned carbon nanotubes. In his process, the nanotubes remained attached to the surface substrate but pushed the catalyst up as they grew.

The graphene/nanotube hybrid came along two years ago. Dubbed ‘James’ bond’ in honour of its inventor, Rice chemist James Tour, the hybrid features a seamless transition from graphene to nanotube.

According to Rice University, the graphene base is grown via chemical vapour deposition and a catalyst is arranged in a pattern on top. When heated again, carbon atoms in an aerosol feedstock attach themselves to the graphene at the catalyst, which lifts off and allows the new nanotubes to grow. When the nanotubes stop growing, the remaining catalyst (or ‘carpet’) acts as a cap and keeps the nanotubes from tangling.

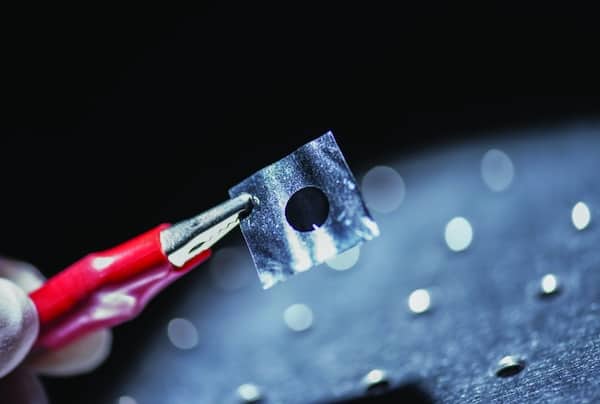

The hybrid material solves two issues that have held back commercial application of dye-sensitised solar cells, Lou said. First, the graphene and nanotubes are grown directly onto the nickel substrate that serves as an electrode, eliminating adhesion issues that plagued the transfer of platinum catalysts to common electrodes like transparent conducting oxide.

Second, the hybrid also has less contact resistance with the electrolyte, allowing electrons to flow more freely. The new cathode’s charge-transfer resistance, which determines how well electrons cross from the electrode to the electrolyte, was found to be 20 times smaller than for platinum-based cathodes, Lou said.

The key appears to be the hybrid’s large surface area, estimated at over 2,000m2 per gram. With no interruption in the atomic bonds between nanotubes and graphene, the material’s entire area, inside and out, becomes one large surface. This gives the electrolyte plenty of opportunity to make contact and provides a highly conductive path for electrons.

Lou’s lab built and tested solar cells with nanotube forests of varying lengths. The shortest, which measured between 20-25 microns, were grown in 4 minutes. Other nanotube samples were grown for an hour and measured about 100-150 microns. When combined with an iodide salt-based electrolyte and an anode of flexible indium tin oxide, titanium dioxide and light-capturing organic dye particles, the largest cells were only 350 microns thick and could be flexed easily and repeatedly.

Tests found that solar cells made from the longest nanotubes produced the best results and topped out at nearly 18 milliamps of current per square centimetre, compared with nearly 14 milliamps for platinum-based control cells. The new dye-sensitised solar cells were as much as 20 per cent better at converting sunlight into power, with an efficiency of up to 8.2 per cent, compared with 6.8 for the platinum-based cells.

Poll: Should the UK’s railways be renationalised?

I think that a network inclusive of the vehicles on it would make sense. However it remains to be seen if there is any plan for it to be for the...