Home Office data obtained by law firm Eversheds Sutherland International has shown that the number of overseas skilled workers moving into engineering roles is on the rise post-Brexit. This reflects a domestic skills shortage in the sector and is indicative of how businesses are strategically adapting their recruitment policies in the context of a post-Brexit market and in response to a tight domestic labour market.

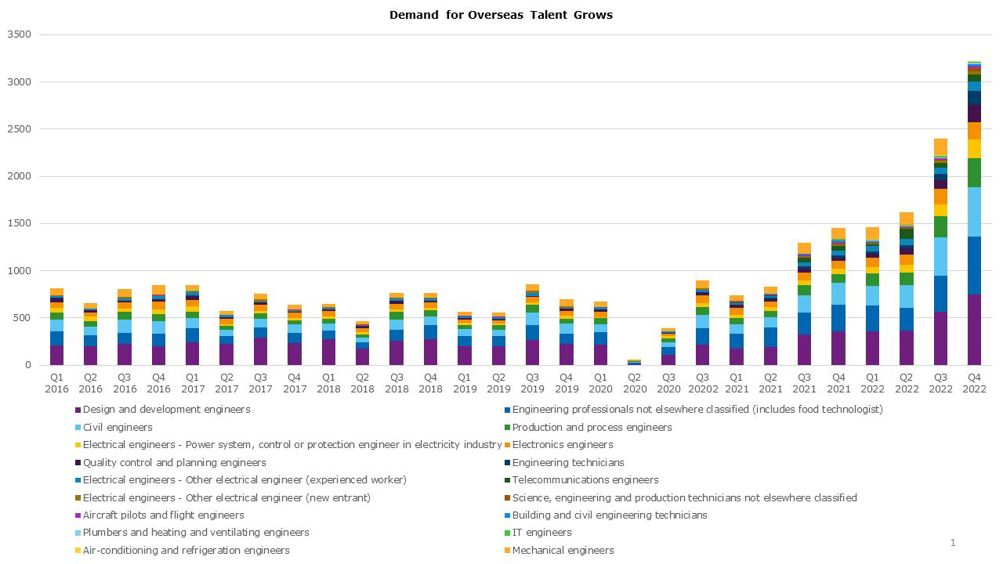

The table below shows categories of engineering roles that overseas workers are performing in the UK – these include both for new skilled worker visas and extensions of skilled worker visas.

The below shows:

- Demand for Production and process engineers increased 252 per cent during the course of 2022

- Demand for Engineering professionals N.e.c increased 58 per cent in the final quarter of 2022

- Demand for Engineering technicians increased 125 per cent in the final quarter of 2022

The engineering sector is largely dependent on talent to grow and, in response to domestic labour market shortages, the sector is using immigration routes to bring in the best talent from around the world. The pool of talent available to the sector has grown significantly since Brexit as the financial disincentive in the form of higher costs of recruiting from outside the EU has been neutralised by virtue of Brexit (and the cessation of free movement of labour) which resulted in the Points Based Immigration system (PBIS) being applicable to those inside as well as outside the EU (and accordingly immigration-related costs of recruiting being the same for those within the EU and those outside).

With this increase in the talent pool, there are strategic recruitment decisions for businesses to make. Whilst many businesses may consider that the new PBIS removes any disincentive from recruiting outside the EU and is therefore beneficial in terms of increasing the available talent, there are other considerations (both financial and otherwise) for businesses when it comes to utilising the immigration system to meet labour demand.

Timing of recruitment may need to be carefully planned to take into account the time it may take for an individual to obtain a skilled worker visa

For example, under the news PBIS each role has a ‘going rate’ salary, this has historically represented an absolute cost to the business when it came to recruiting outside of the EU as salaries would potentially need to be inflated in order for a particular role/individual to be capable of being sponsored. However, in light of the apparent UK labour shortages for the sector (not to mention relatively high domestic inflation and the cost-of-living crisis) and the impact these factors may have on domestic recruitment (e.g. in respect of salary demands from UK candidates), this may no longer be the disincentive it once was.

Whilst the potential increased pool of talent available to the sector may be attractive to businesses, there are practical steps which will need to be considered and ‘costs’ that businesses will need to factor in to their planning. These ‘costs’ are not necessarily just financial but may include internal process and systems modifications which will need to be implemented as a direct consequence of utilising the immigration routes to meet labour demand. Practical considerations businesses may need to consider are as follows:

1. Timing of recruitment may need to be carefully planned to take into account the time it may take for an individual to obtain a skilled worker visa and also time it may take for a business to obtain a sponsor licence, if they don’t have one already (i.e. businesses are required to hold a valid sponsor licence for the particular immigration route in order to sponsor workers from outside of the UK and this does come at a cost);

2. For each sponsored worker there are sponsorship compliance duties that will need to be adhered to in order for a business to retain its sponsor licence and continue employing sponsored workers, which may necessitate the upskilling of HR personnel within the business if not already familiar with immigration processes;

3. Business will need to ensure that they have robust right to work practices in place in order to prevent any illegal working;

4. When recruiting from outside of the UK, additional consideration will need to be given to those roles requiring certain certifications and the extent to which there is international divergence and equivalence in terms of standards for such qualifications. Procedures may need to be implemented to verify and test the equivalence of overseas certificates/qualifications in order to enable an individual to undertake a particular role – this could cause potential delays and will need to be considered before roles are offered;

5. As well as the practical ‘costs’, there are also additional expenses that business will need to factor into their recruitment budgets when considering sponsoring workers from outside of the UK. These include:

-

- the cost of assigning a certificate of sponsorship (CoS)

- the immigration skills charge

- visa application costs

- the immigration health surcharge

Generally speaking, the visa application fees and immigration health surcharge are usually borne by the individual rather than the business, albeit due to the extension of the fee and surcharge to EU individuals it remains to be seen whether the market standard practice will change and businesses will routinely assume these financial costs.

Businesses will also need to be aware of potential increased salary costs. As each role under PBIS has a ‘going rate’ salary set by UKVI, businesses may need to increase salaries being offered for particular roles in order for them to be capable of sponsorship – along with this comes employee relations issues if there are discrepancies between UK and non UK employee salaries. However, in light of domestic inflation and the cost of living crisis, businesses may consider that increased salary costs are inevitable irrespective of where labour is recruited from.

Although as referred to above there are ‘costs’ involved in sponsorship, utilising the PBIS will potentially allow the engineering sector access to a greater pool of talent and may help to combat the domestic skills shortage the sector is experiencing facilitating the future growth of the sector.

Louise Lightfoot (above left), partner and Pia Carr (above right), senior associate in the employment and immigration team at Eversheds Sutherland

Poll: Should the UK’s railways be renationalised?

I think that a network inclusive of the vehicles on it would make sense. However it remains to be seen if there is any plan for it to be for the...