When you open your Christmas present this year it might not be obvious that you are helping a revolution in sports science. Some of the most popular presents are likely to be mobile phones, games consoles and computer games, all of which are contributing to an array of devices that will help us monitor and measure the athlete of the future.

Apparently, there are around 5 billion phones in the world currently, with the latest containing accelerometers, gyroscopes, GPS, electronic compasses and megapixel cameras (some with video at 120 frames per second or high definition resolution). While Apple’s iPhone 4S is currently the fastest selling electronic gadget of all time, selling over 1 million units per day in the first few days after launch, one of its predecessors was Microsoft’s Kinect gaming device with over 100k per day for 60 days. Prior to that there was Nintendo’s Wii with over 90 million sales to date.

Early adopter

The point is that, in science, we use a lot of the devices now taken for granted in phones and consoles. Accelerometers and gyroscopes have been used for many years to measure the acceleration, rotation and inertial forces of moving bodies, particularly in engineering. The manufacture of these sensors in huge quantities has brought down their cost significantly. Sport is an early adopter and has always used the latest in technologies so expect to see your Christmas present used on an athlete near you very soon.

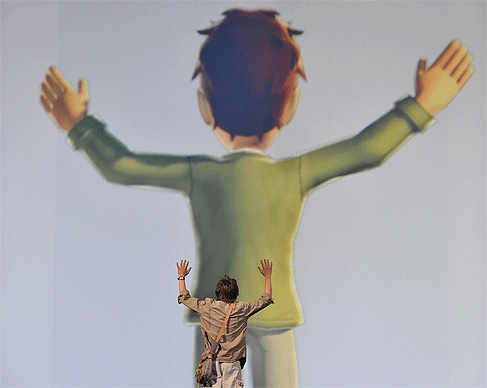

Microsoft’s Kinect is probably the game changer (sorry for the pun). It uses an infra-red projector to project a seemingly random array of invisible-to-the-eye dots up to a distance of around 10 m. An infra-red camera picks up the dots and complex algorithms use the distortion of the patterns to calculate depth. This is combined with a standard colour camera to give a 3D view of the world. The device detects the gestures of the user and uses them to control a game.

What is really exciting is that the Kinect measures the 3D world and can measure surfaces, track motion and even put a rudimentary skeleton on real-time analysis. All for less than £100. Conventional gait labs can cost 500-1000 times this, admittedly with much better accuracy, but with the general limitation that it is restricted to an indoor space with an athlete made up with reflective markers on each segment.

We’ve done some initial tests with the Kinect and it appears that it can measure the volume of a torso to around 2 per cent accuracy and the position of the centre of mass to around 0.5 per cent. Joint angles are not quite as good at the moment, particularly for the lower body (the Kinect appears to optimised for the upper body) but early use shows promise. Apple appears to have taken out a patent on 3D cameras for its iPhone and no doubt other manufacturers will be thinking the same; this raises the possibility that we will soon be able to measure the 3D world around us at reasonable cost.

A phone is not just for Christmas

There is a conference just after Christmas on wearable sensors - not just for sport but for health related uses too. After all, performance improvement is relative: for an elite athlete it might be measured in hundredths of a second while for someone in rehabilitation it might be simply to walk again.

So when you open that present on Christmas Day, marvel at the technology within and imagine the possibilities - someone may already be writing the app for your phone.

Mandate sets 2030 date for use of sustainable aviation fuel

I do hope this doesn't cause costs to UK aviation to rise and lose business to those staying on fossil fuels.