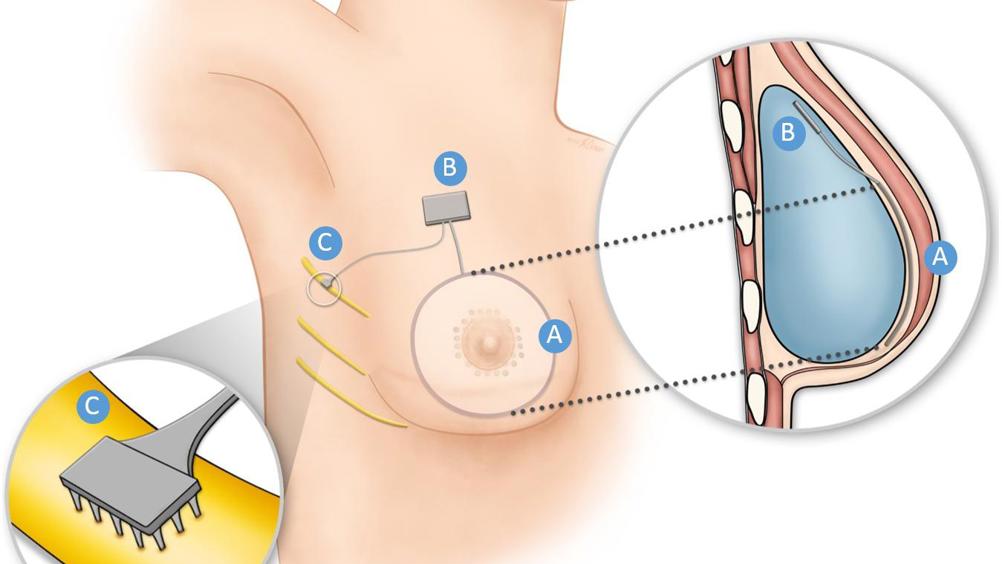

Bionic breast seeks to return sensation after mastectomy

Researchers at the University of Chicago have received $4m to further develop a bionic breast that provides a sense of touch, helping cancer survivors preserve sexual function.

The Bionic Breast Project is bringing together neuroscientists and biomaterials engineers to build an implantable device that will restore sensation to the breast after mastectomy and reconstructive surgery. Electronic components will connect to the nervous system through an array of electrodes called a C-FINE device that wraps around the intercostal nerves in the chest. In trials, small, capped electrical leads will be exposed under the patient’s armpit, with researchers testing the device by delivering electrical impulses through the leads and patients reporting on the corresponding sensations.

Roughly a third of those diagnosed with breast cancer undergo a mastectomy, where one or both breasts are surgically removed from the body. As well as leaving many patients - up to 77 per cent - with reduced sexual function, the rapid decision-making processes often required can also be a source of trauma, according to Dr Stacy Tessler Lindau, director of the Program in Integrative Sexual Medicine at the University of Chicago Medical Center.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

UK Enters ‘Golden Age of Nuclear’

The delay (nearly 8 years) in getting approval for the Rolls-Royce SMR is most worrying. Signifies a torpid and expensive system that is quite onerous...