Copper nanoflowers power clean fuel production

Cambridge and Berkeley researchers have attached copper nanoflower electrocatalysts to an artificial leaf to produce clean fuels and chemicals that are useful to a range of industries.

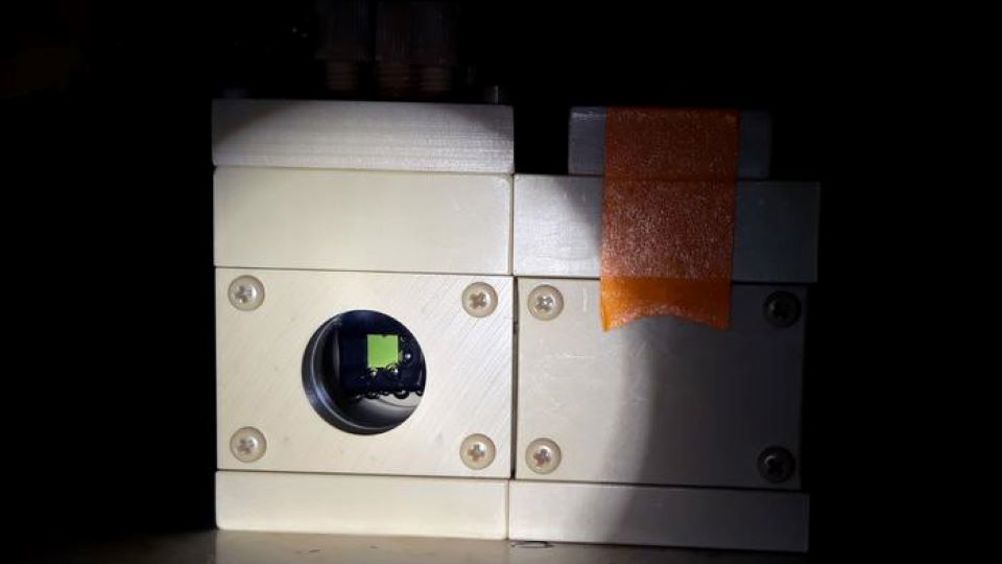

The device from researchers at Cambridge University and the University of California, Berkeley combines a light-absorbing ‘leaf’ made from perovskite with a copper nanoflower catalyst to convert carbon dioxide into useful molecules.

Unlike most metal catalysts, which convert CO₂ into single-carbon molecules, the copper flowers enable the formation of more complex hydrocarbons with two carbon atoms, such as ethane and ethylene, which are key building blocks for liquid fuels, chemicals and plastics.

Almost all hydrocarbons currently stem from fossil fuels, but the method developed by the Cambridge-Berkeley team results in clean chemicals and fuels made from CO2, water and glycerol – a common organic compound – without any additional carbon emissions. Their results are detailed in Nature Catalysis.

The study builds on the team’s earlier work on artificial leaves, which took inspiration from photosynthesis.

“We wanted to go beyond basic carbon dioxide reduction and produce more complex hydrocarbons, but that requires significantly more energy,” said lead author Dr Virgil Andrei from Cambridge’s Yusuf Hamied Department of Chemistry.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Well let´s do a little experiment. My last (10.4.25) half-yearly water/waste water bill from Severn Trent was £98.29. How much does not-for-profit Dŵr...