The graphene-based sensor, developed by researchers at Southampton University in collaboration with the Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (JAIST), can detect individual carbon dioxide (CO2) molecules and volatile organic compound (VOC) gas molecules.

These chemicals, which can be found in low concentrations of parts per billion (ppb) in materials, furniture and household goods in homes, offices, schools and cars, are believed to contribute to health problems associated with so-called sick building syndrome.

These pollutants are extremely difficult to detect with existing sensors, which can only detect gases with concentrations of parts per million.

The sensor, developed by a group led by Prof Hiroshi Mizuta, who has a joint appointment at both Southampton University and JAIST, can detect a single CO2 molecule as it bonds to the graphene – a process known as adsorption.

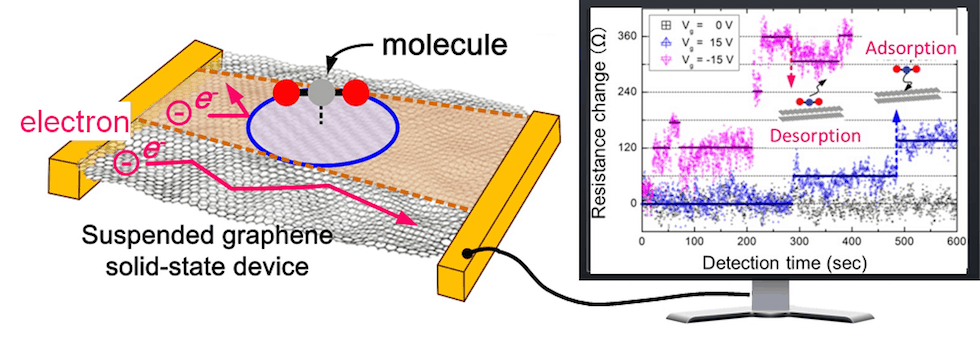

The sensor, presented in a paper in the journal Science Advances, consists of a 300 nanometre-long graphene beam suspended above a gold electrode formed on a silicon substrate, according to Mizuta. As a gas molecule is adsorbed onto the graphene, it alters the electrical resistance of the material to a detectable degree, he said.

“In order to detect very dilute gas molecules quickly, we apply an electric field from the silicon substrate and accelerate their adsorption onto the graphene, which gives us a detection time of only a few minutes,” he said.

To build the device, the researchers applied a voltage from the bottom electrode to create an electrostatic force that pulls the central part of the suspended graphene beam down towards it, said Mizuta. “This leads to two slanted graphene beams in suspension, with built-in tensile strain,” he said.

This design holds the graphene beams firmly in position, even when the electric field is applied, he said.

Members of the research group recently developed thin-film, graphene-based switches that require extremely low voltages, and can be used to power electronic components. Mizuta and the research group are now hoping to combine the two technologies, to create ultra-low power sensors capable of detecting individual molecules.

Poll: Should the UK’s railways be renationalised?

I think that a network inclusive of the vehicles on it would make sense. However it remains to be seen if there is any plan for it to be for the...