Transplant rejection sensor paves way for body-integrated electronics

New technology under development at The Ohio State University is paving the way for low-cost electronic devices that work in direct contact with living tissue inside the body.

The first planned use of the technology is a sensor that will detect the very early stages of organ transplant rejection.

Paul Berger, professor of electrical and computer engineering and physics at Ohio State, explained that one barrier to the development of implantable sensors is that most existing electronics are based on silicon, and electrolytes in the body interfere with the electrical signals in silicon circuits. Other semiconductors might work in the body, but they are more expensive and harder to manufacture.

‘Silicon is relatively cheap… it’s non-toxic,’ Berger said in a statement. ‘The challenge is to bridge the gap between the affordable, silicon-based electronics we already know how to build, and the electrochemical systems of the human body.’

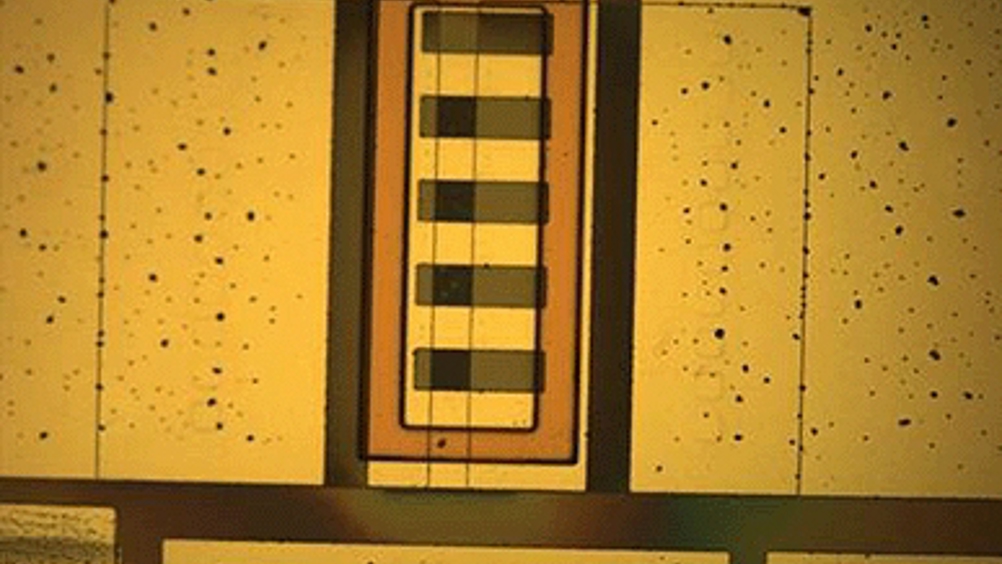

In a paper in the journal Electronics Letters, Berger and his colleagues describe a new, patent-pending coating that that they believe will bridge that gap.

In tests, silicon circuits that had been coated with the technology continued to function, even after 24 hours of immersion in a solution that mimicked typical body chemistry.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...