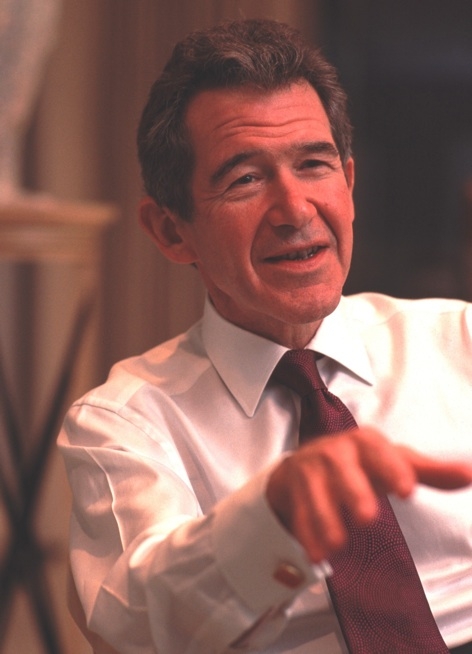

Lord Browne, president of the Royal Academy of Engineering

The former BP chief says that the next generation of engineers have plenty to get excited about

As one of the most successful businessman of his generation, Lord Browne has a gift for charming the likes of Margaret Thatcher and Vladimir Putin. His laid-back manner is disarming and so too is his fervour for work. At once serious and charismatic, it’s clear to see how he convinced some of the most powerful people in the world to engage in business. And now he’s planning to do the same for engineering.

‘I have a fairly trivial request for government,’ said the 62 year old. ‘Whenever they talk about science, would they please talk about science and engineering. Use three words not one… I remember my former senior vice-president Dame Wendy Hall said to me that it was rather like being in industry as a woman a long time ago. People would address everybody as men. She said it’s just like this, they talk about science and they forget to talk about engineering, and that needs to change.’

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of premium content. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our premium content, as well as the latest technology news, industry opinion and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Well let´s do a little experiment. My last (10.4.25) half-yearly water/waste water bill from Severn Trent was £98.29. How much does not-for-profit Dŵr...