One of the occasional perks of writing for a technology title is invitations to the opening of new exhibitions at the Science Museum, and a chance to see them away from the crowds that tend to descend during peak times. Press openings begin well before the museum opens to the public, so the event is always preceded by a wander through the deserted halls to reach the Wellcome Wing, where they are located. It's a spooky experience; even under full lighting the massive wheels and shafts of the steam engines in the lobby gather shadows to themselves, and the Apollo lunar module in the dimly lit Space Hall looms overhead like an angular spider.

This faint atmosphere of dread suits Museum's new exhibition, Top Secret: From Ciphers to Cyber Security, which opens to the public today (10th July, 2019). From the start, we are left in no doubt that keeping secrets is a matter of life and death: after a brief introduction to the history of ciphers from ancient times in the form of wall captions, the exhibit proper opens in the trench-scarred fields of Flanders, with the development of the "Fullerphone" by the British Army to ensure that communications from trench telephones could not be intercepted by the German army.

Subsequently, it details the terror of the early Zeppelin air raids, with incendiary bombs falling from the sky, and the use of radio triangulation to locate the airships as they flew overhead, revealing that the mere fact of communication itself, regardless of its content, can be a cause of vulnerability.

The exhibition is the result of an unprecedented collaboration between the museum and GCHQ, the government’s centre for security in communication. Celebrating its centenary this year, the organisation is now on the front line of the battle to ensure cyber security, whose importance was underlined in 2017 with the Wannacry ransomewhere virus attack that caused severe problems to institutions including the National Health Service. A laptop deliberately infected with Wannacry sits isolated in a Perspex case in the exhibition, labelled with an assurance that it can't infect anything else.

The collaboration began when the museum staged an exhibition to celebrate the centenary of the birth of Alan Turing, as GCHQ had provided some surviving relics of the Bletchley Park era of code-cracking, explained its director, Sir Ian Blatchford. He assured the visiting journalists that this heralded a new era of openness that GCHQ had decided was essential to its future success, and took care to note that the organisation is staffed by "normal people". GCHQ's director, Jeremy Fleming, began his introduction to the exhibition by commenting that he was "shockingly normal".

These assurances were belied somewhat by a request from museum’s press chief that GCHQ staff should not be photographed as we went around the exhibition. They can be recognised by their red lanyards, we were told; the fact that those lanyards supported labels bearing the letters GCHQ in bold black capitals was a little more of a giveaway. I can reassure readers that the wearers of these labels indeed looked perfectly normal and were pleasant and seemingly quite human when I spoke to them. However, I cannot offer any photographic evidence, so you’ll have to take my word for it.

This is an absorbing exhibition packed full of artefacts which have not been seen in public before. One of these, a cabinet -sized device called 5-UCO, even came as a surprise to GCHQ, because they thought it had been destroyed. Developed in 1943, 5-UCO (pronounced 5-YOU-KO, the label helpfully tells us, making it sound endearingly like a droid from Star Wars) kept the intelligence derived from decoded messages from Enigma machines and the even more secret deciphered Lorenz messages, between Nazi high command and even Adolf Hitler himself, completely secret when they were being sent to military commanders in the field. Exhibition curator Liz Bruton told The Engineer that this showed how decryption turns into military intelligence, but underlines that this is useless unless it can be securely shared. The machine was so secret that it was assumed destroyed to conceal the very fact of its existence, Fleming said.

"It's important to remember that GCHQ is not a museum," Liz Bruton explained. "They only preserve things for continued study and training. Artefacts like the ones we have on show here are used to instruct staff involved with decryption on the history of what they are doing." Bruton added that such is the aura of secrecy still surrounding GCHQ and its work, the visitors might find the very fact that the exhibition has been staged at all to be the most surprising facet of their visit.

Not that the exhibits themselves have no surprises. As well as the expected section explaining the history of the work of Bletchley Park, displays include the secured telephones used by Winston Churchill during World War II, the Pickwick phone used for conversations between Harold Macmillan and John F. Kennedy during the Cuban missile crisis, and a chunky briefcase telephone used by Margaret Thatcher to tell the Ministry of Defence that the rules of engagement during the Falklands war in 1981 had been changed, leading directly to the controversial sinking of the Argentine warship General Belgrano.

Equally surprising is the recreation of part of the home of Peter Kroger and his wife Helen. They had in fact encoded themselves; rather than the antiquarian bookseller and housewife they appeared to be, they were in fact Soviet spies Morris and Lona Cohen, and their suburban bungalow in the suburb of Ruislip (decorated with rather horrible chintzy wallpaper and a lurid flowery carpet if the recreation is accurate, although I have my doubts: I find it unlikely that the doormat would have had a welcome message on it in Cyrillic letters) was their centre of operations, where the head of what became known as the Portland spy ring, a Russian intelligence officer using the cover identity of Canadian businessman Gordon Lonsdale, would often visit.

The spy ring used microdots to conceal documents (these would be hidden as punctuation in the antique books 'Kroger' dealt in), and the exhibit shows the modified talcum powder tin they used to transport the microdots. It also shows the British nuclear submarine whose details the spies sent to the Soviet Union, allowing them to accelerate their own development. The spies were convicted in 1961, with the ‘Krogers’ and ‘Lonsdale’ eventually exchanged for British spies who had been imprisoned by the Soviets. Morris and Lona Cohen were celebrated as heroes on their return, with stamps issued in their honour.

Although this section of the exhibition sits slightly uneasily with exhibits on ciphers and cyber security, it reminds us that the word cryptography derives from crypt, a place where people are buried, and that the spies had willingly buried themselves under layers of deception and ugly home decoration.

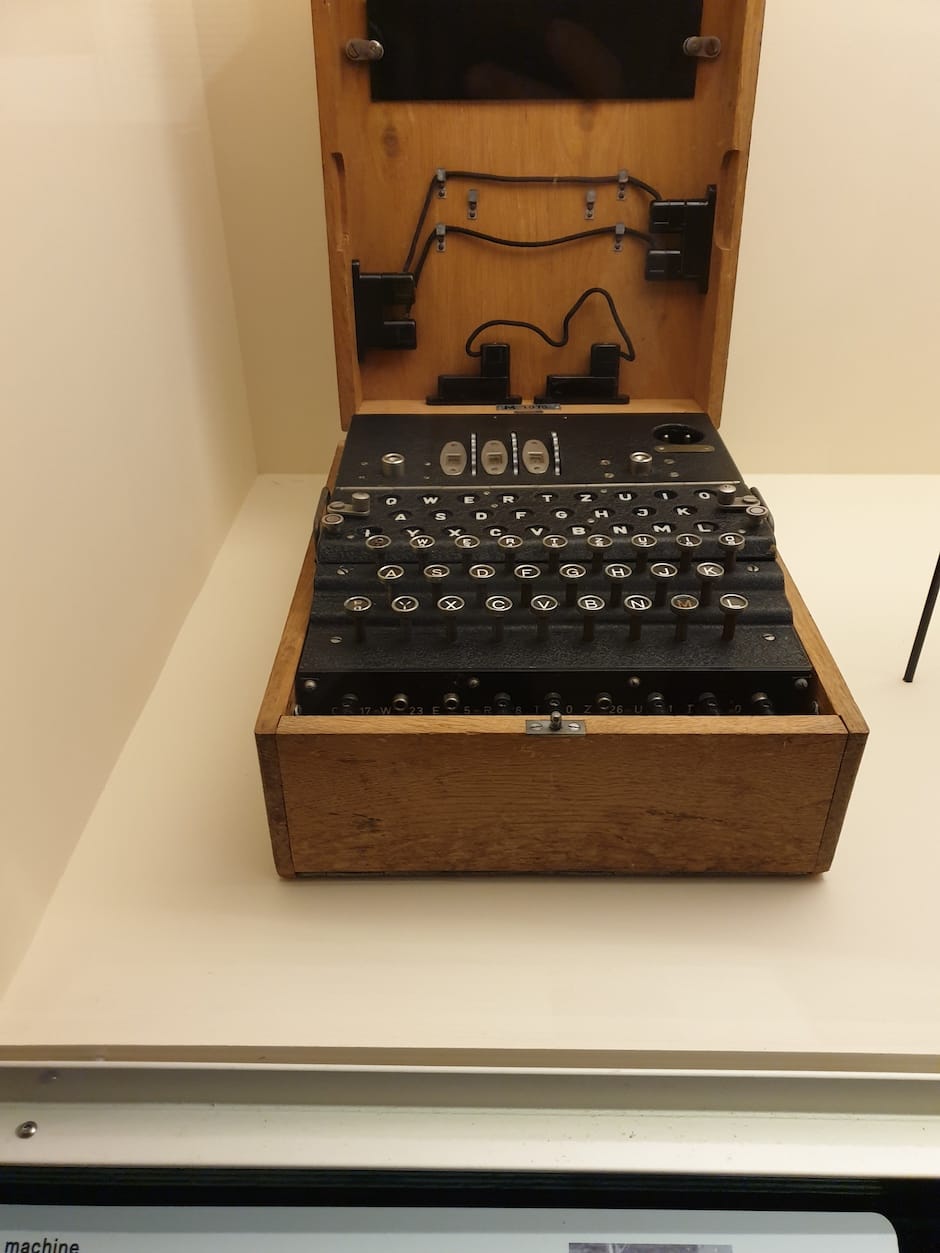

Liz Bruton said that part of the goal of the exhibits was to show how technology had developed to keep pace with the development of secrecy, and how science played a role in that. "We've been at pains to talk about the role of Polish mathematicians in cracking the Enigma code," she said. "They had knowledge of the civilian version of the Enigma machine, which had been used to keep industrial secrets safe, and they used that to reverse engineer the military version. Their work was also instrumental in developing the bombe mechanical calculation devices that were used to crack encoded messages at Bletchley Park. And that led directly to the development of the electronic computer." The key for Enigma and the Lorenz cipher machine were changed every 24 hours, she explained "so it would be no use having a machine that took 100 hours to crack the code. Speed was vital."

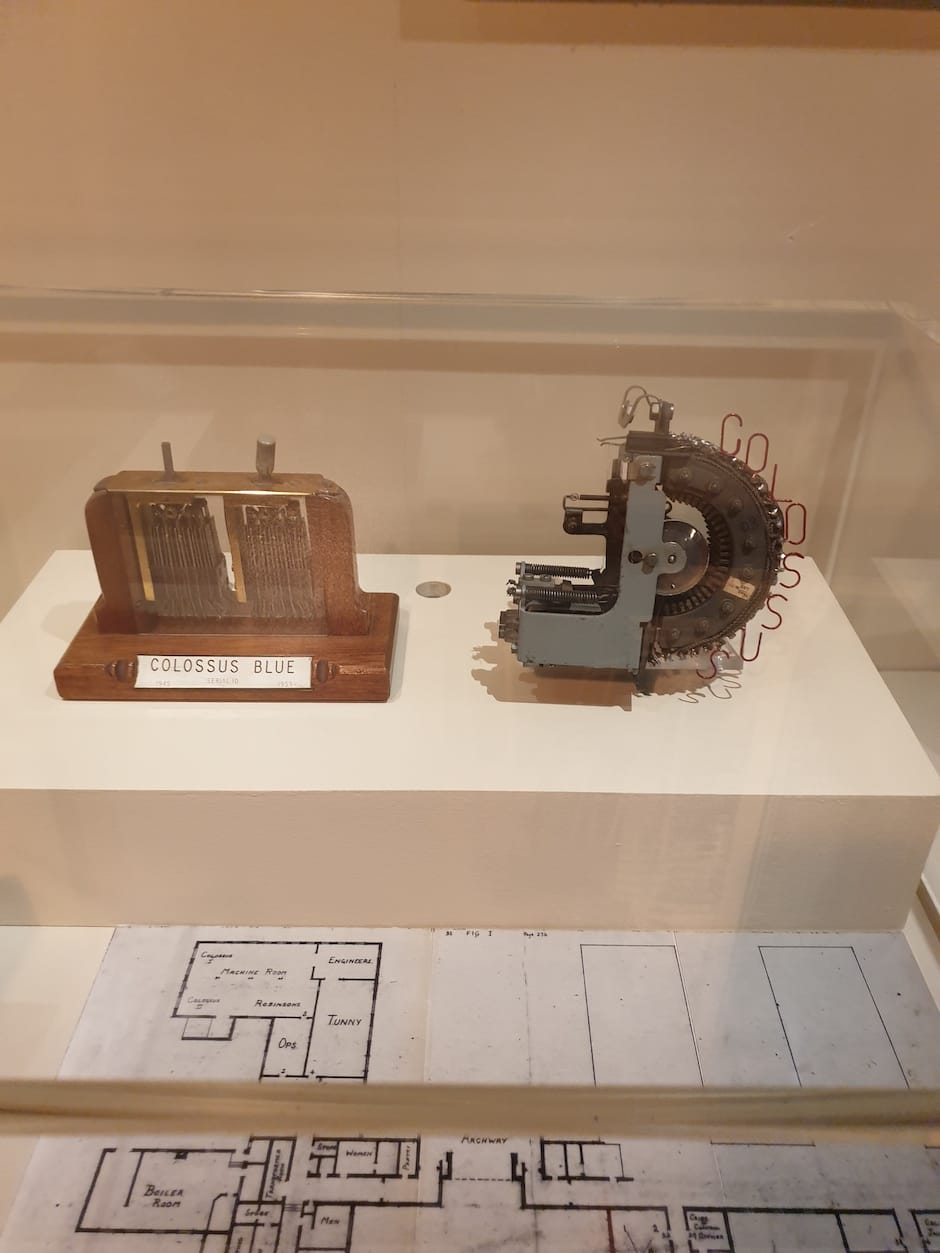

Telecommunications engineer Tommy Flowers realised that thermionic valves (the forerunners to transistors), which had been previous he thought of as being too unstable to use, were in fact completely reliable if they were kept running rather than turned off and switched on at intervals, and use this insight to design the Colossus computer that was used at Bletchley to quickly crack Lorenz messages, helped by mistakes made by a German radio operator that provided the key to the code. Two rare surviving Colossus components are on display.

The exhibition is indeed highly informative on this aspect of technology development, and the use of maths and randomness in cryptology continues to this day. Generators of randomness on show include tiles plucked from a bag by code makers in World War II, chaotic pendulums and arrays of lava lamps used to generate random sequences.

Things take a decidedly chilling turn as the exhibition moves towards the present day, with the recreation of a "liquid bomb" for the trial of terrorists who planned to use them to bring down aircraft, with the result that we still cannot today take more than 100ml of any liquid onto a plane and have to go through elaborate and annoying security theatre before boarding. “My Friend Cayla”, a doll designed to be able to answer children's questions by connecting via a mobile phone to access Wikipedia entries, but which turned out to be easy to intercept via Bluetooth and which did not delete any of the data it extracted, stares blankly across the gallery.

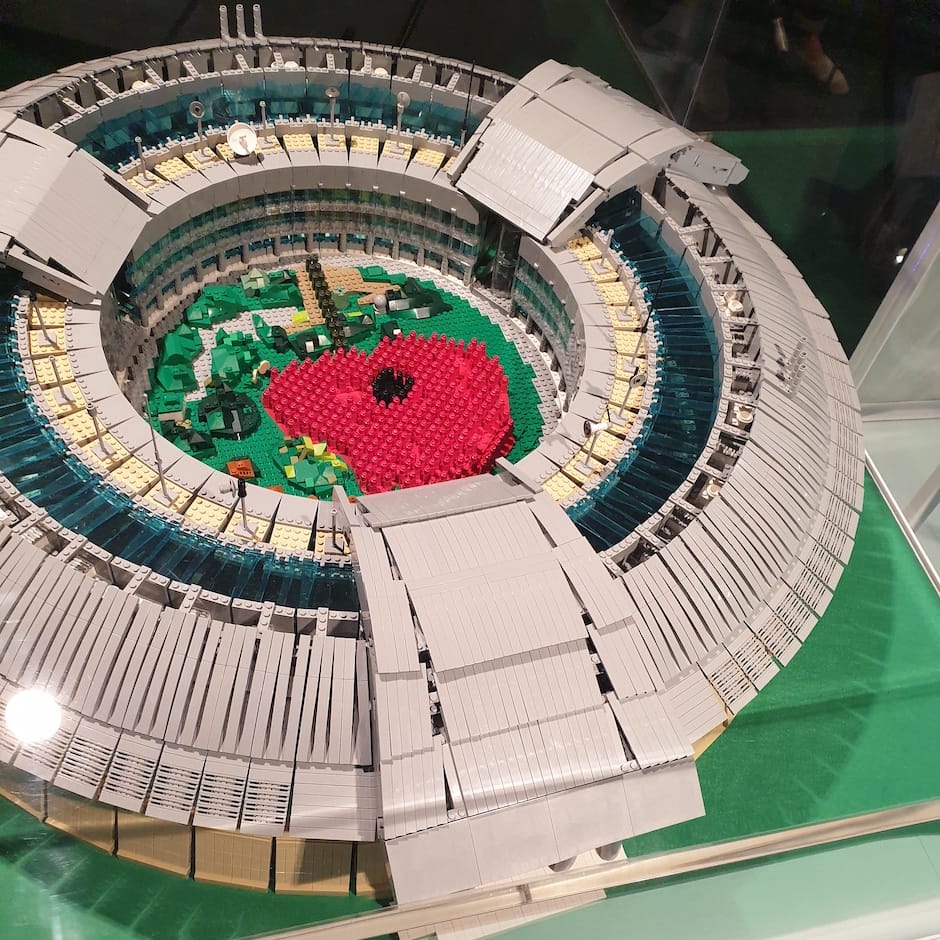

GCHQ attempts to make itself friendlier in the exhibition with a recreation of its iconic doughnut building in Cheltenham built from Lego. This is an impressive feat, although itself an enciphering, making a building full of lethal secrets (although, of course, handled by completely normal people) appear to be as harmless as a children's toy.

The exhibition ends with a sample of dust from computer parts ground up by GCHQ to destroy any data they might have contained. Ian Blatchford revealed that he had spoken about this with author Philip Pullman, equating this dust to the metaphorical 'Dust' Pullman wrote about in his "His Dark Materials" trilogy, where it represents experience gathered over a human lifetime, interpreted by some characters as sin.

Top Secret: From Ciphers to Cyber Security runs until 23 February 2020 at the Science Museum and will then open at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester before touring internationally. For information on visiting the exhibition and its accompanying events, including discussions on the future of quantum computing, visit the Science Museum's website.

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...