Recently there has been much news on plastics, particularly for packaging, their uses and where they end up after use.

We have heard calls for a plastic-free society as well as reports that householders don’t know what they can recycle on account of a lack of standardisation across the UK, and that even if the public do put their waste out for recycling, as little as 9% of plastic is actually recycled following collection. To understand why this happening and why plastic is such a popular material we need to examine its origin, uses and how recycling works.

As a material, plastics are very useful and this is particularly the case in food packaging and other consumer goods where we see their extensive use. Plastics offer a leak-free, hygienic environment, they can be manipulated in shape, the entire packaging process can be automated, and thousands of tonnes of food waste and money can be saved every year.

As with all materials it isn’t the plastic that is the problem, it is how we make, use and manage the whole lifecycle of the product. When deciding on what material to use for packaging it should be appropriate for the product. For instance, if you have a product that is perishable within a couple of days, then packaging it in a material that will not biodegrade for hundreds of years is not an appropriate use of materials or resources (unless there are hygiene or medical reasons for this).

There are many types of plastics that are part of the ever increasing challenge of plastic waste in the UK. These include resins, farm and fishing plastics, Polyetheylene terephthalate: PET (found in plastic bottles), high density polyethylene: HDPE (used in electronics, car parts, construction materials, water pipes, furniture and household items like bins and buckets), as well as polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride and many others.

This article will focus on domestic waste, but as the Institution of Mechanical Engineers recommended back in 2009 in our Waste as a Resource report, we should be creating resource management strategies that deal with household waste, commercial and industrial, construction demolition and excavation wastes because just focusing on household waste, although politically important, is just 14% of our total waste.

Plastics are made from oil and gas, and according to a recent UN report, if consumption continues at the current rates, may account for 20% of oil use globally by 2050. However, the British Plastics Federation states that the current use of oil and gas for plastics is only about 1.5%. It is likely that the UN’s predicted increase will be due to the decreasing use of oil and gas in other sectors, meaning a rise in that used by the plastics industry.

One key issue when it comes to managing recycling and waste more generally in the UK is that it is a devolved issue for Wales, Scotland, England and Northern Ireland, with each region having different strategies and plans. This is further complicated by local authorities being able to decide how they meet the devolved government targets.

For example, in Wales there are 22 unitary authorities (the administrative division of local government) and 22 different recycling schemes, even though the local authorities may share waste management facilities. The number of different schemes means that the quality of plastics collected, and whether there is a market to recycle them, is variable.

When it comes to understanding the success of recycling targets across the UK this too inconsistent. Taking Wales as an example again, the quantity of waste recorded as recycled is based on waste that is prepared for recycling, not that which is actually recycled. This means that in order to create better markets for recyclable materials, we have to drill down further into this type of data to understand where complete recycling occurs and where it does not.

It would then be possible to begin to address those gaps and create better schemes that meet the needs of those buying waste materials for reuse and recycling.

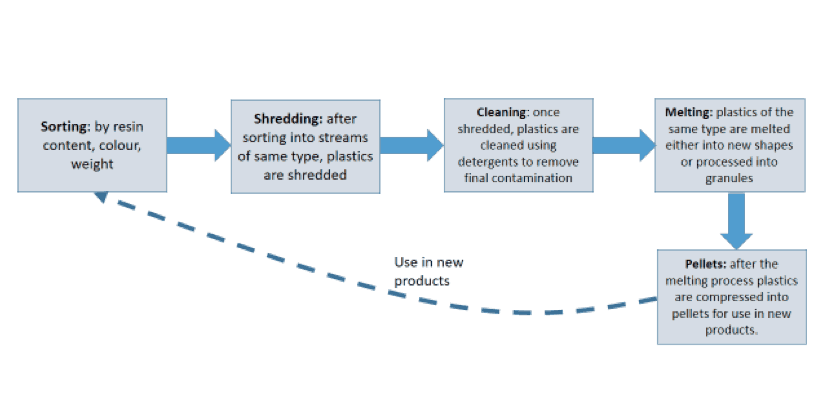

Once plastics that are recyclable are collected the process to turn them into a new product or reusable plastics is shown in the figure below:

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Well let´s do a little experiment. My last (10.4.25) half-yearly water/waste water bill from Severn Trent was £98.29. How much does not-for-profit Dŵr...