When the alloy is heated during welding, its molecular structure creates an uneven flow of its constituent elements - aluminium, zinc, magnesium and copper - which leads to cracks along the weld.

In an advance that could benefit the automotive industry, engineers at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering have infused titanium carbide nanoparticles into AA 7075 welding wires, which are used as the filler material between the pieces being joined. A paper describing the advance was published in Nature Communications.

Using the new approach, the researchers are said to have produced welded joints with a tensile strength up to 392 megapascals. Post-welding heat treatments could further increase the strength of AA 7075 joints, up to 551 megapascals, which is comparable to steel.

AA 7075 can help increase a vehicle’s fuel and battery efficiency and it is already used to form plane fuselages and wings, where the material is generally joined by bolts or rivets. Similarly, the alloy has been used for products that don’t require joining, such as smartphone frames.

But the alloy’s resistance to welding, specifically, to the type of welding used in automotive manufacturing, has prevented it from being widely adopted.

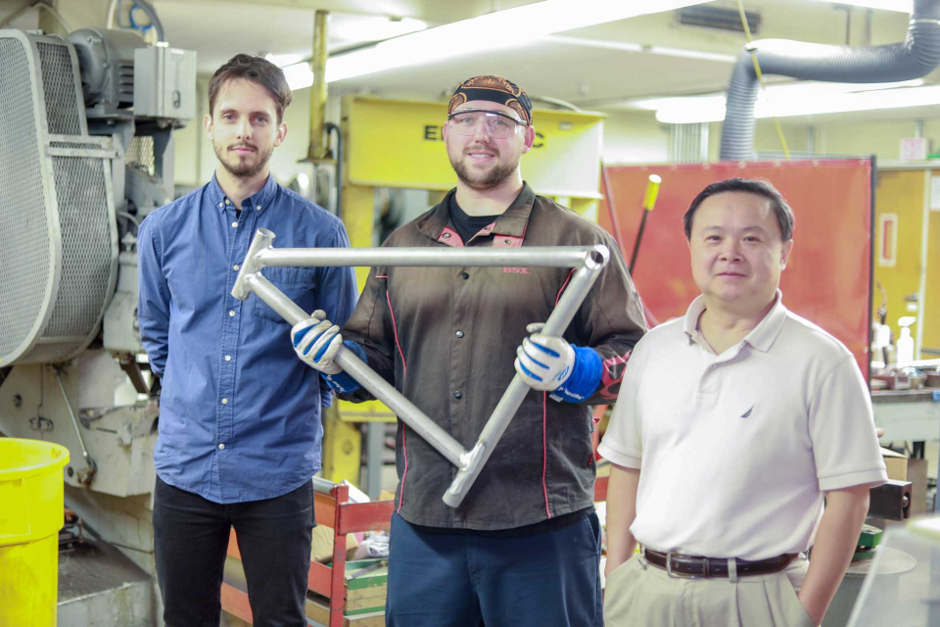

“The new technique is just a simple twist, but it could allow widespread use of this high-strength aluminium alloy in mass-produced products like cars or bicycles, where parts are often assembled together,” said Xiaochun Li, UCLA’s Raytheon Professor of Manufacturing and the study’s principal investigator. “Companies could use the same processes and equipment they already have to incorporate this super-strong aluminium alloy into their manufacturing processes, and their products could be lighter and more energy efficient, while still retaining their strength.”

The researchers are working with a bicycle manufacturer on prototype bike frames that would use the alloy, and the new study suggests that nanoparticle-infused filler wires could also make it easier to join other hard-to-weld metals and metal alloys.

Poll: Should the UK’s railways be renationalised?

I think that a network inclusive of the vehicles on it would make sense. However it remains to be seen if there is any plan for it to be for the...