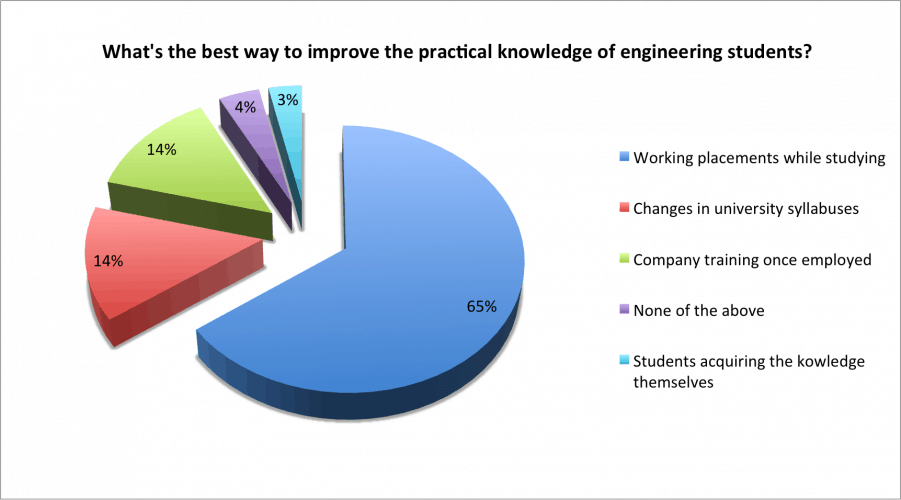

With engineering students returning to their studies, we asked our readers how best to address the the practical skills deficit many believe is lacking in those entering the workplace.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the overwhelming majority (65%) believed that work placement to coincide with academic study was the preferred option. The joint second most popular responses (14% each) were changes to university syllabuses and on-the-job training once employed.

Just 3% of respondents felt the best solution was for students to develop their own practical skills, despite many of our readers commenting in the past that this was how they had gained hands-on experience before entering third-level education. As ever, please give us your thoughts below. This is undoubtedly a debate that will rearing its head again in the future.

Poll: Should the UK’s railways be renationalised?

Rail passenger numbers declined from 1.27 million in 1946 to 735,000 in 1994 a fall of 42% over 49 years. In 2019 the last pre-Covid year the number...