An injectable biosensor could one day be used for continuous, long-term monitoring of people on substance abuse treatment programs.

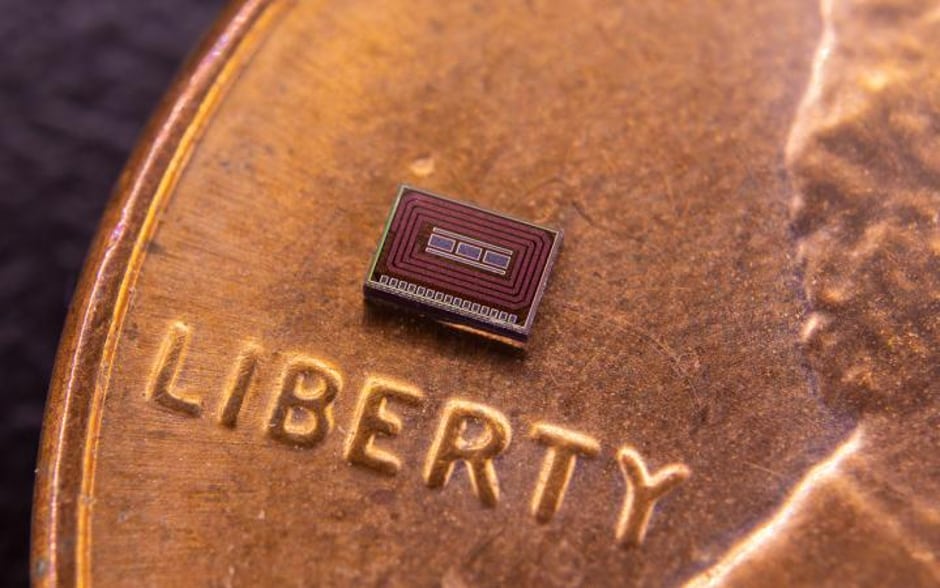

Alcohol monitoring chip can be implanted under surface of skin (Credit: David Baillot/UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering)

Developed by engineers at the University of California San Diego, the chip is small enough to be implanted just beneath the surface of the skin and is powered wirelessly by a wearable device.

"The ultimate goal of this work is to develop a routine, unobtrusive alcohol and drug monitoring device for patients in substance abuse treatment programs," said Drew Hall, an electrical engineering professor at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering who led the project. Hall's team presented this work at the 2018 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC) on April 10, 2018 in San Diego.

According to UCSD, one of the challenges for patients in treatment programs is the lack of convenient tools for routine monitoring. Breathalysers, currently the most common way to estimate blood alcohol levels, require patient initiation and are not that accurate, Hall said. Blood tests are the most accurate method, but need to be performed by a trained technician. Tattoo-based alcohol sensors that can be worn on the skin are a promising new alternative, but they can be easily removed and are only single-use.

"A tiny injectable sensor - that can be administered in a clinic without surgery - could make it easier for patients to follow a prescribed course of monitoring for extended periods of time," Hall said.

The biosensor chip measures roughly one cubic millimetre in size and can be injected under the skin in interstitial fluid, which is the fluid that surrounds the body's cells.

It contains a sensor coated with alcohol oxidase, an enzyme that selectively interacts with alcohol to generate a by-product that can be electrochemically detected. The electrical signals are transmitted wirelessly to a nearby wearable device such as a smartwatch, which wirelessly powers the chip. Two additional sensors on the chip measure background signals and pH levels. These get cancelled out to make the alcohol reading more accurate.

The researchers designed the chip to consume a total of 970nW as they didn’t want it to have a significant impact on the battery life of the wearable device.

“And since we're implanting this, we don't want a lot of heat being locally generated inside the body or a battery that is potentially toxic," Hall said.

One of the ways the chip operates on such ultra-low power is by transmitting data via backscattering, which occurs when a nearby device – smartwatch or similar wearable - sends radio frequency signals to the chip, and the chip sends data by modifying and reflecting those signals back to the smartwatch. The researchers also designed ultra-low power sensor readout circuits for the chip and minimised its measurement time to three seconds, resulting in less power consumption.

The researchers tested the chip in vitro with a setup that mimicked an implanted environment. This involved mixtures of ethanol in diluted human serum underneath layers of pig skin.

For future studies, the researchers are planning to test the chip in live animals.

"This is a proof-of-concept platform technology. We've shown that this chip can work for alcohol, but we envision creating others that can detect different substances of abuse and injecting a customised cocktail of them into a patient to provide long-term, personalised medical monitoring," Hall said.

The team has filed a provisional patent on this biosensor technology.

UK defence spending ramps up for warfighting readiness

It would be good if much of this money was used to develop (easily) adaptive and affordable forming manufacturing technologies - rather than buying...