Described in the journal Organic Electronics, the technology involves manufacturing the solar cell, the substrate that supports it, and a protective overcoating all in one step. The substrate is made in place and never needs to be handled, cleaned, or removed from the vacuum in which production takes place. This minimises exposure to dust and other contaminants that could degrade the cell’s performance.

“The innovative step is the realisation that you can grow the substrate at the same time as you grow the device,” said Vladimir Bulović, MIT’s associate dean for innovation and one of the paper’s lead authors.

According to the researchers, the entire process takes place in a vacuum chamber at room temperature and without the use of any solvents. Both the substrate and the solar cell are “grown” using chemical vapour deposition, or CVD. This involves vapourising monomers and introducing them to the chamber where they link up to form a thin layer of polymer.

For the initial proof-of-concept experiment, the team used a common flexible polymer called parylene for both the substrate and the overcoating.The commercially available plastic is widely used to protect biomedical devices and printed circuit boards. An organic material called DBP (tetraphenyldibenzoperiflanthene) was used as the primary light-absorbing layer.

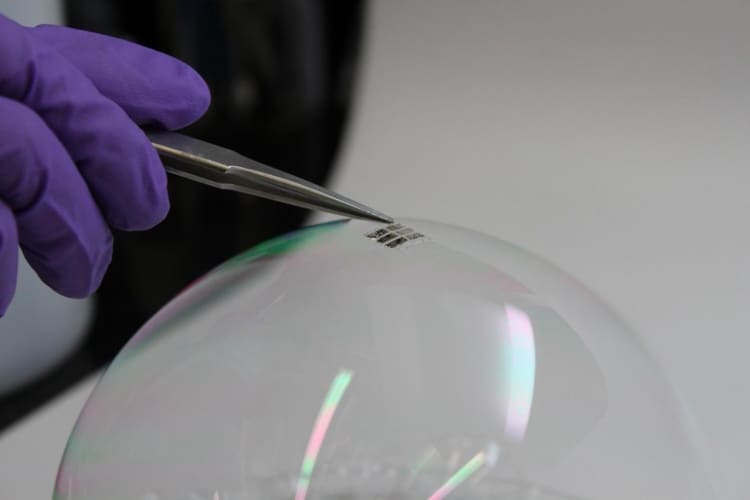

The result is a cell just two micrometres thick, about one-fiftieth of the thickness of a human hair. To demonstrate how lightweight the cells are, the researchers placed a working cell on top of a soap bubble without it bursting. The team also claims that different materials could be used for the substrate and encapsulation layers, as well as for the solar cell itself.

While the technology is a long way from commercial viability, future applications could include wearable electronics, as well as lightweight solar cells for the aerospace industry.

“It could be so light that you don’t even know it’s there, on your shirt or on your notebook,” said Bulović.

“These cells could simply be an add-on to existing structures.”

Klein Vision unveils AirCar production prototype

According to the Klein Vision website, they claim the market for flying cars will be $1.5 trillion by 2040, so at the top end $1 million per unit that...