UK firm Newtecnic is using engineering know-how to turn architectural dreams into reality

Tucked away in the heart of Cambridge’s city centre sits the R&D department of one of the UK’s most interesting engineering firms.

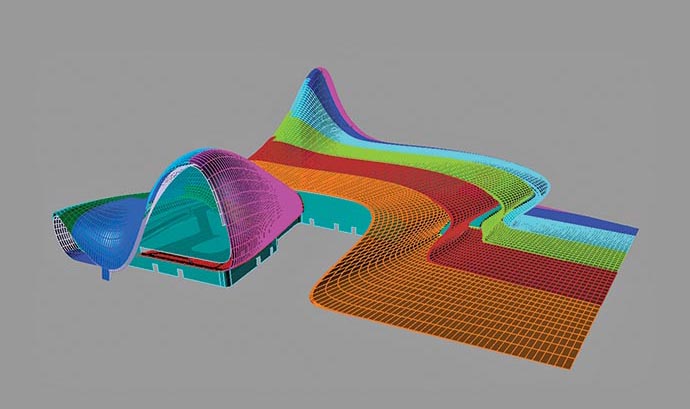

Founded in 2003, Newtecnic is behind some of the world’s grandest civil projects, from the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre in Baku, Azerbaijan, to the Grand Theatre of Rabat in Morocco. Working alongside clients including Zaha Hadid Architects, it is helping to shape the public spaces of undeveloped regions across the globe.

“We provide the engineering design for ambitious, large-scale projects, which are usually

high-profile projects,” Andrew Watts, Newtecnic’s CEO, told The Engineer.

According to Watts, Newtecnic’s role is to understand the architectural vision but also be sympathetic to what engineers and contractors can feasibly achieve. With a combination of cutting-edge design tools, building techniques and materials, the company is challenging the boundaries of modern construction.

“The work is all done from first principles,” Watts explained. “In other words, we design structures and buildings as if we’ve never done them before.”

As well as Morocco and Azerbaijan, Newtecnic has worked extensively in the Middle East, where large-scale public projects are sprouting in a desert bloom of steel and glass.

However, despite working for clients in some of the world’s wealthiest states, the realities of financial constraint still apply.

“Nobody throws money and just says ‘Build your dream,’” said Watts.

“They tend to be quite commercial rates of construction so, in order to make that work, we have to do a lot of research into reducing the quantity of material and the weight of the structures.

“When you reduce weight, you start to enter the world of mechanical engineering… it becomes much more like designing an aircraft, for instance, than a traditional, heavy building.”

Newtecnic has an industrial partnership with the University of Cambridge’s Department of Engineering, where Watts has maintained links as an alumnus. The company’s R&D team uses advanced 3D BIM (building information modelling) systems to digitally explore a project, then creates physical mock-ups in its structures lab. This rapid prototyping and wind tunnel testing is unusual for the civil sector, according to Watts.

“What may be fairly standard in transportation-led engineering fields we’re now introducing into building design,” he said.

It’s not just the design phase where Newtecnic is innovating. The company employs a range of composite materials, including UHPC (ultra high-performance concrete), GRC (glassfibre-reinforced concrete) and FRP (fibre-reinforced plastic).

“Why would you use those materials?” Watts posited. “Because you can mould them. You can make them into things you’ve never made before. You don’t need to extrude or squash to make them all the same. You can make them in a way that is very specific to the project.”

Yet to serve their dues

Engineers know how traditional concrete and plastics react over time, but these relatively new materials have yet to serve their dues. To counteract that novelty, Newtecnic puts them through accelerated ageing to see how they change over a lifetime.

The company’s building philosophy is also designed to reduce the high proportion of waste material that construction often leaves behind. According to Watts, this can be as much as 50 per cent on some projects.

And the savings are not limited to quantities of concrete and steel. Transporting materials is one of the biggest energy inputs for a building’s construction; cutting the amount of material needed can reduce journeys to and from the build.

As for the finished products, it seems that less can indeed be more. Newtecnic’s buildings are among the most groundbreaking designs seen anywhere and have seeped into the public consciousness in ways that buildings rarely do. The Zaha Hadid-designed cultural centre in Baku is perhaps the most prominent example, its delicate sweeping curves standing in contrast to the stark Soviet blocks that surround it. In a recent Google Doodle that celebrated the late architect, it was the Baku building that a smiling Hadid stood before.

Another major collaboration between Newtecnic and Zaha Hadid Architects is now nearing completion. The King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD) Metro Station will be the jewel in the crown of Riyadh’s new mass transport network, due to open in 2019. Its futuristic design should make an apt centrepiece for such an ambitious project but, according to Watts, buildings like this are possible only as a direct result of the R&D carried out by Newtecnic in the UK.

“We often have to work on these [materials] a year or two before they’re needed,” he explained. “So we have to invest in things that may end up not being used on the project but, we hope, will maybe get used on something else.

“We work much more like a tech company, which would consider it very normal to invest large amounts of its profit into research.”

Much of the company’s landmark work has taken place in emerging economies, where public space is plentiful. As they seek to make their mark on the 21st century, many of these nations are pumping money into major civil projects.

“Russia, the Middle East and China: they’ve acquired a lot of wealth in a short space of time and they’re building the future, building their future cities,” said Watts.

“They think the urban community should extend to cultural projects that you can virtually inhabit, as it were. Art galleries, theatres, the transport system: all these are felt to be part of the fabric of the cities that they’re creating. They’re not just add-ons.”

Many of the locations call for innovative approaches to temperature management. Whereas some buildings are fitted with HVAC systems to simply deal with temperature load at given times of the year, Newtecnic takes a different approach. During the design phase it carries out CFD (computational fluid dynamics) studies to better understand the natural airflow within the structures and how various building elements interact. It then develops algorithms to explore how those conditions can be optimised.

“It’s very much a high-tech version of what I learned as an undergraduate, in learning how to create an environmental strategy for a building,” said Watts.

“What needs heating? What needs cooling? What needs lots of air changes? What needs very few air changes? And how can you tie them all up together so that they work as one big mechanism?”

Form dictated by function

Here, form is often dictated by function, with not only internal spaces tweaked to reduce the HVAC load but buildings’ facades shaped to serve their occupants. Reminiscent of Formula One engineer Adrian Newey’s automotive designs, the results are generally striking, with the algorithms calling for unconventional features to manipulate the airflow in just the right manner.

”They end up, sort of, not exactly generating themselves but the form is strongly influenced by performance, and often ends up looking quite nice,” Watts said. “It resonates with the architects when they can see they’re getting an original expression through a technical process rather than through a visually driven process, or something they’ve seen somewhere else.”

As for the future, Watts regards the open expanses of Australia as a major new frontier. Newtecnic is working on a large housing development in northern Queensland, as well as two towers in the southern part of the state, and another project in Sydney.

“We’ve had a couple of years where everything seemed to be gravitating into Saudi Arabia. Then it was China. Now it seems to be Australia,” he said.

“The mood in Australia at the moment seems very progressive, the way the built environment is being developed.”

IEA report claims batteries are ‘changing the game’

The weight and bulk of static batteries, even domestic units, is immaterial. The IEA's trilemma is illustrated here:-...